Common Good

Dozens of Ohio courts have set up special sessions to assist people suffering from mental illness who end up in the criminal justice system. It’s a collaborative effort in which courts join forces with treatment providers, law enforcement, and others to connect people with much-needed services such as medication, counseling, housing, and transportation.

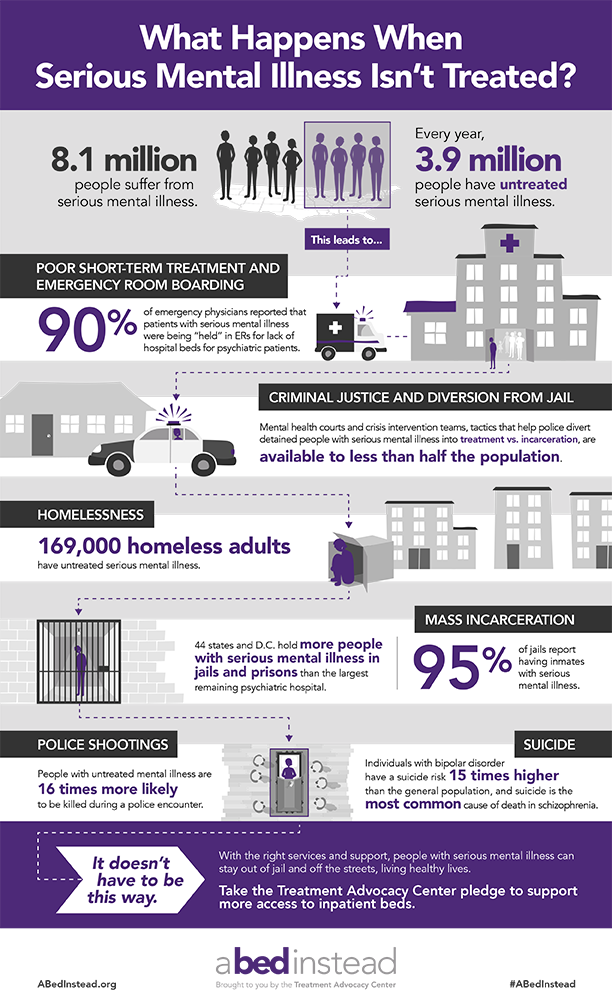

More than 383,000 adults with serious mental illnesses are being held in a U.S. jail or prison, according to the nonprofit Treatment Advocacy Center. Of the 64,000 people jailed or imprisoned in Ohio in 2005, more than 10,000 were estimated to have serious mental illnesses.

In the Fairfield Municipal Court, Judge Joyce Campbell faced the grim consequences of the number of people committing crimes connected to untreated mental illness. In 1999, she presided over the initial appearance and preliminary hearing on a homicide stemming from a workplace shooting. The woman charged with shooting her co-worker had been in the criminal justice system in Fairfield before – for an assault two years earlier. Because of her severe mental illness, the woman was found not guilty by reason of insanity for the assault and released back into the community. There was no follow-up on needed care nor was she connected to local mental health providers, Judge Campbell said. Untreated, the woman later killed a former co-worker at their place of employment.

Frustrated, Judge Campbell began looking for solutions. After reading an article from Miami University in Ohio about therapeutic law, she visited a mental health docket in Florida and talked with stakeholders in her community. In 2001, she launched Ohio’s second mental health court. The first mental health court in Ohio was started by Judge Elinore Marsh Stormer in the Akron Municipal Court the same year.

“Society brings its problems to the courts,” Judge Campbell said. A 2016-2017 policy paper from the Conference of State Court Administrators (COSCA) points out the disturbing dilemma: “Jails and prisons have replaced mental health facilities as the primary institutions for housing persons suffering from mental illness.”

Courts have responded over the past two decades by seeking more effective approaches when someone with a mental illness lands in the criminal justice system. As of this May, which is Mental Health Month, Ohio has 39 mental health dockets in common pleas and municipal courts. That number includes two courts designed to deal simultaneously with mental health and substance abuse problems. State courts also offer other types of dockets for specialized issues – such as drug courts and veterans courts – in which mental health concerns may be an issue, as well as 14 juvenile courts that have implemented specialized dockets to handle either mental illness alone or mental health and substance abuse issues together.

To run a mental health docket, state courts must follow Ohio Supreme Court standards, which lay out a detailed structure rooted in a non-adversarial approach.

Multiyear Obligation Undertaken by Participants

Judge Campbell has the capacity to work with 25 people on her mental health docket. Many have been charged with traffic offenses, but other cases involve misdemeanor offenses of assault or disorderly conduct as well as probation violations.

“The goal is not to have people in jail or prison who shouldn’t be there,” she said.

Individuals in Fairfield Municipal Court can avoid a criminal conviction if they are eligible and choose to participate for approximately two years in the mental health diversion program overseen by the court. In Fairfield, and many other communities, victims of the alleged offense or offenses must agree to the diversion. If the participant completes Fairfield’s two-year program, any charges will be dismissed, and the participant can ask to have the case record sealed.

It’s a comparable setup in Hamilton County Common Pleas Court. Judges Lisa C. Allen and Tom Heekin each set aside an afternoon every week to run mental health dockets. Combined, they can handle up to 48 participants.

A treatment team meets before each court session. Treatment teams are part of every mental health court docket, and they pool knowledge from diverse sectors – law enforcement, case managers, licensed treatment providers, defense attorneys, prosecutors, the specialized docket judge, probation and parole officers, and others as needed.

Medina County Common Pleas Court

Judge Allen sees defendants accused of non-violent felonies, often theft and drug charges. The treatment team connects each person with appropriate mental health treatment after evaluating the individual’s distinct needs. Other essential services, such as housing, employment, education, transportation, and medical care, are also identified and obtained if possible.

Judge Allen is impressed by what participants are able to accomplish. She described a woman in her 50s suffering from bipolar disorder who had a terrible heroin and cocaine problem and was homeless for years. Now engaged in the court’s mental health docket, the woman is clean and has her own apartment, Judge Allen said.

“It takes a lot of guts to take part in the program,” she said.

And it’s a substantial commitment for participants. The Supreme Court’s standards require them to appear in court at least twice a month during the first program phase and to appear regularly after that. The standards recommend, though, that these problem-solving courts set more stringent requirements – weekly appearances during the initial phase and at least monthly meetings throughout the rest of the program.

“This isn’t a get-out-of-jail-free card,” said Judge Joyce Kimbler, who can manage up to 20 people on the mental health docket in Medina County Common Pleas Court. “There’s a high level of accountability – more accountability than a typical probation sentence.”

Encouragement and Penalties Are Fundamental Tools

Incentives are offered and sanctions are imposed to keep participants on track. Judges are permitted to adapt to suit the circumstances.

Expectations had been spelled out for a young man on Judge Kimbler’s mental health docket. He hadn’t made progress, and Judge Kimbler asked him at a hearing how he was spending his time. “Doing nothing,” he said. She pressed him for specifics, and he told her he had been playing video games and watching YouTube. The judge decided to take away his computer until he completed three of his tasks. It worked.

“I think he managed his stress by turning to those activities,” Judge Kimbler said. “As the judge, you consider what incentives will motivate the participant, and which sanctions the person might respond to. I’ve found they respond best to clear-cut guidelines.”

Judges nudge and encourage, and when capable participants don’t follow the rules, Judge Campbell says she displays her “Mrs. Potato Head angry eyes.” Occasionally, increased court appearances, community service, a few hours in a holding cell, or even jail time, if appropriate, will get a person’s attention, she said, adding that she will do what’s needed to assist a participant in complying with the program requirements.

“But it’s not an adversarial process,” she noted. “It’s a nurturing, supportive environment. It’s a smarter, less-expensive, and more humane way to deal with people involved in the criminal justice system as a result of mental illness.”

As a prosecutor, Judge Allen saw a lot of “frequent flyers” cycling repeatedly through the courts, some struggling with unaddressed and untreated mental illness. She didn’t think it made sense.

“Jail is not a good mental health hospital,” she said.

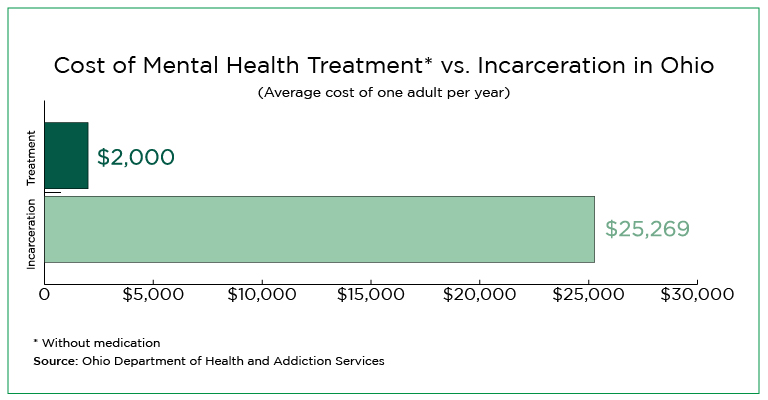

With mental health dockets, though, the public saves the considerable cost of housing people in jails and prisons, she explained.

“Participants in these programs aren’t draining society’s resources and aren’t committing crimes, but instead are more likely to become contributing members of their communities,” Judge Allen said, noting that 90 percent of her court’s participants stay out of the criminal justice system after completing the diversion program. “It’s a better way to deal with this population.”

Hamilton County Common Pleas Court

Untreated Mental Health Issues Have Costs for Society

The COSCA report, authored by Judge Milton L. Mack Jr., administrator of the Michigan courts, backs up this perspective. Prisoners with mental illness serve longer sentences, receive greater numbers of probation and parole violations, and are more often repeat offenders, Judge Mack wrote, citing U.S. Department of Justice statistics.

In Ohio, taxpayers pay $69.23 per day to house an offender in prison and $75 each day to jail a person, according to the Ohio Department of Health and Addiction Services. That amounts to $25,269 per year to imprison one person, or $252.7 million to cover the cost of holding the estimated 10,000 Ohioans with mental illness in prison.

Perspectives Have Evolved Over Time

The dramatic and consequential shift in thinking has taken time and effort, former Justice Evelyn Lundberg Stratton noted. As a trial judge in Franklin County, she saw arrest after arrest of mentally ill people who were “falling through the cracks” without any services. As an Ohio Supreme Court justice, she formed the Advisory Committee on Mental Illness and the Courts in 2001. The mental health courts in Akron and Fairfield were in place, setting the example.

The committee, which grew from 10 to 50 members over time, created the opportunity for different agencies and community services to collaborate on the issue, Stratton said. She and a police lieutenant drove across the state talking to groups about the benefits of mental health dockets and of training law enforcement to identify mental illness in people they encounter on the streets and to find alternatives to arrest, if possible, to assist mentally ill people. At the time, only 100 police officers had completed “crisis intervention training” (CIT), but today more than 10,500 officers are trained in the techniques, she said.

Now in private practice, Stratton is still engaged on mental health issues and is the program director for Stepping Up Ohio, the state arm of a national initiative to reduce the number of people with mental illnesses in jails. She highlighted some of the beneficial outcomes of these efforts throughout the years.

“Families who once were afraid to call police about mentally ill relatives now feel more comfortable reaching out for assistance because of greater police training about mental illness,” she said. “And because financial resources are always a challenge for courts and in jails and prisons, reducing the number of people with mental illnesses in jails and prisons has been one positive impact of mental health dockets.”

Opportunity for Transformation

Ohio municipal and common pleas judges see firsthand the upsides of mental health dockets every week in their courtrooms.

“I wish I could offer the program to more people,” Judge Allen noted. “It’s gratifying to see the light come back in their eyes.”

“It’s the best thing I do as a judge,” said Judge Campbell. “For the participants, the program reaffirms for them that they are human beings, and that they’re worthy of being alive and having a life.”