Closing Civil Justice Gaps

Courts throughout Ohio have opened help centers to assist the public with questions about non-criminal cases. The need for guidance is substantial, and centers at two municipal courts – which have assisted thousands in just a few years – serve as models for tackling this growing challenge.

Darrilyn took a seat at one of the small, round, white tables. Across from her were two attorneys looking over the Hamilton County Municipal Court’s docket. She wanted to understand the latest update in her case. The city where she lives had filed a lawsuit against her and her husband for past-due municipal income taxes. The city said they owed thousands of dollars, and the court entered a default judgment in the city’s favor because the couple hadn’t responded. That brought Darrilyn to the court’s Help Center a few months ago for guidance.

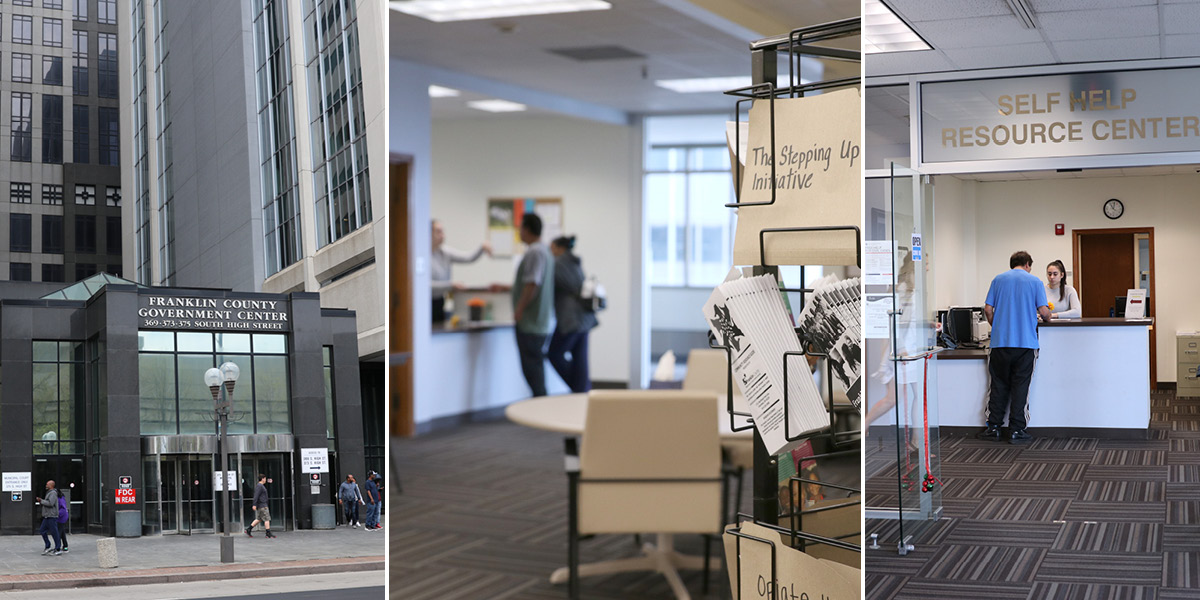

The center sits on the first floor of the Hamilton County Courthouse in downtown Cincinnati. As they thread through the building’s security line, visitors pass the glassed entrances to the center and the clerk’s offices – located next to each other.

Two Municipal Courts Create Centers to Assist Public

Rob Wall, the center’s director and staff attorney, and his team have assisted individuals representing themselves in civil lawsuits since September 2017, when the center opened its doors. It was the second municipal court in Ohio to offer services for self-represented litigants.

The first – the Franklin County Municipal Court Self Help Resource Center – launched in May 2016. Robby Southers, its managing attorney, and Wall both said the inspiration for their centers grew from a recommendation made by the Ohio Supreme Court’s Task Force on Access to Justice, convened by Chief Justice Maureen O'Connor. The task force’s 2015 report suggested such centers as a way to help address the unmet needs of people who can’t afford legal services.

Across the state, other courts, particularly those dealing with domestic relations and juvenile matters, have implemented help centers as well. In Hamilton and Franklin counties alone – which encompass the large metropolitan areas of Cincinnati and Columbus – the need appears to be vast.

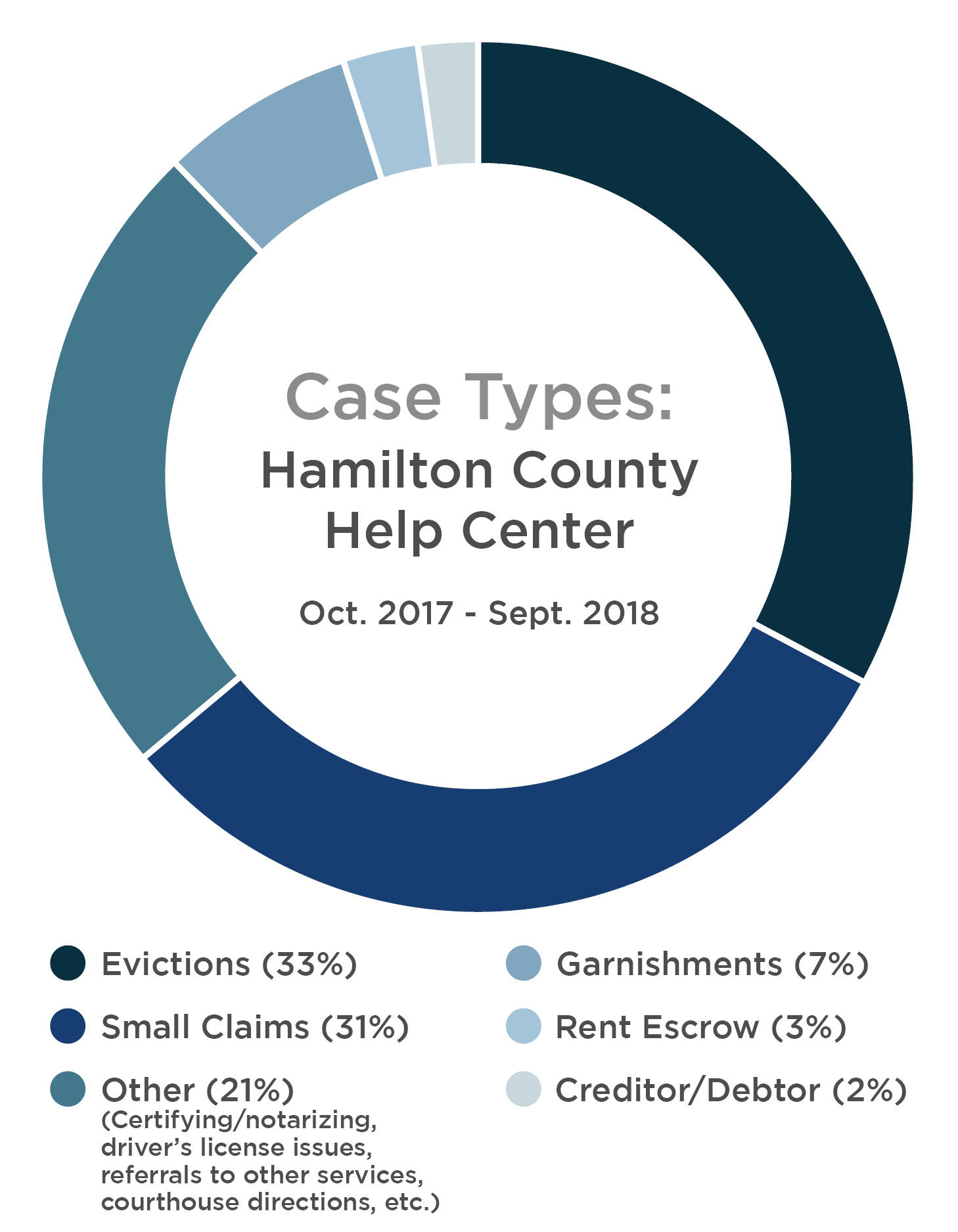

Hamilton County logged 12,392 visitors in its first 12 months – roughly 1,000 each month, or 50 per day. Questions on landlord/tenant issues topped the list, from both residents and owners. Of the almost 4,000 landlord/tenant matters, 3,624 – 92 percent – involved evictions. On one Monday in mid-April alone, the staff dealt with questions about 50 eviction cases. Following close behind are inquiries related to small claims, such as auto accidents, unpaid wages, and security deposit returns.

In its first 22 months, Franklin County’s center helped 1,391 people. Since moving to a more central courthouse location a year ago, though, the center has assisted 5,303 individuals – a nearly fourfold increase in half the time. Based on the climbing numbers, Southers expects they’ll see more than 6,000 people this year.

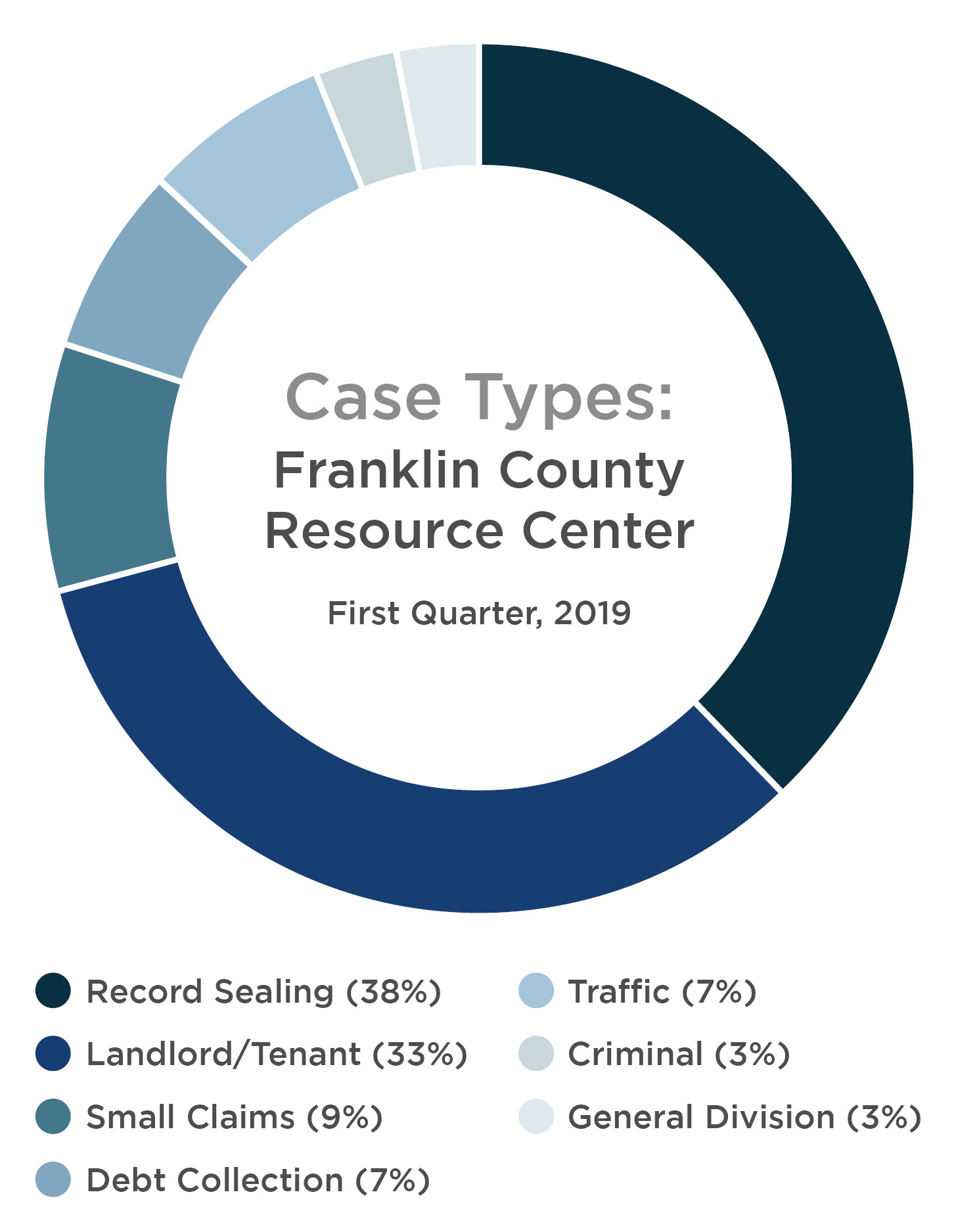

The staff of Franklin County’s center also spend much of their time addressing landlord/tenant issues – ranging from 33 to 58 percent of its work, depending on the quarter. Demand is rising, though, for assistance with sealing and expunging records, likely due to changes in Ohio law that took effect last fall, Southers said. Those questions reached 38 percent of the total in the first three months of 2019.

How much help the centers can provide depends on their model.

Franklin County Informs People about Choices

At the Franklin County Municipal Court, the judges and leadership were most comfortable with a setup focused on useful information, Southers said. He and the center’s staff attorney, Tori Edwards, determine the issue and point the visitor in the right direction. That may be locating the right paperwork, figuring out who in the courthouse can assist best, or identifying helpful resources, whether inside the court or out in the community.

“It’s options counseling,” Southers explains.

On an April morning, two visitors who stepped through the center’s entrance on the municipal court’s sixth floor asked for guidance on the center’s most-requested topics. A veteran had questions about an eviction notice, and a man asked about sealing a misdemeanor offense.

The large, airy space has several tables where visitors can sit to work on paperwork or take a break from a stressful experience in court, Southers said. Visitors can log on to nearby computers to access information they might need, such as bank statements to show the court what types of income they do, or don’t, have.

Of course, some people would benefit from legal advice, and the staff will pinpoint other places visitors may be able to find help, such as a legal aid organization. To further address that need for its visitors, the center collaborates each month with the Legal Aid Society of Columbus to host a brief advice clinic in the center.

Offering Legal Advice Broadens Hamilton County’s Services

Back in Cincinnati, Wall explains that he worked with Darrilyn a few months ago to draft a formal request to the court asking to set aside the default judgment so she could have a chance to answer.

Helping Darrilyn draft her motion is an example of the limited legal advice the Hamilton County center provides. To get that in-depth guidance, visitors must schedule an appointment with Wall or one of the center’s two volunteer attorneys. Wall often helps people prepare for hearings, fill out paperwork, and draft court filings, such as complaints for small claims court and answers in debt collection cases. In the first year, the center offered legal advice to 888 people, most of them referred internally from magistrates handling cases.

“To address the unmet needs of litigants in civil cases, courts are tasked with something very difficult,” Wall said. “A limited legal advice clinic was a good choice for us in Hamilton County.”

Aftab Pureval, Hamilton County Clerk of Courts, made starting a help center for the municipal court part of his platform when he ran for the position in 2016. Pureval said the public frequently directed questions to magistrates in court and the staff in the clerk’s office, but they aren’t able to give answers that would be considered legal advice. It struck him as odd that there was nothing to help people through their experiences with the court.

In researching how other courts statewide and nationally handled this issue, he found that some courts offered kiosks or built informative, robust websites.

“There’s definitely a place for those options, but they were too broad and too impersonal for our community,” he said.

They also looked to the Ohio Rules of Professional Conduct for guidance. Rule 6.5 acknowledges the difficulties of doing checks for conflicts of interest in non-profit and court-annexed limited legal services programs, Wall said.

“We only give legal advice after someone has filled out terms of service and intake sheets,” he explains. “I typically review a case before sitting down with someone. A secondary purpose of doing this is to spot potential conflicts. If I am unsure, I may look up the name of an opposing party in our records to see if I’ve previously given them legal advice.”

Front Desk Focus in Hamilton County Is Information Only

At the Hamilton County center’s front counter, though, where dozens line up daily with questions, the limits are clear – “legal information only,” said Wall.

Ashley Thomas, a paralegal and center employee, and the law school students who assist at the center are trained on these boundaries. They give disclaimers to visitors, and if questions arise requiring more than information, they offer to schedule individuals for legal advice appointments. The staff frequently turn to the nearby file slots filled with forms that have proved useful. They also screen for whether visitors might qualify for other legal services, such as legal aid or mediation, and refer them as needed.

Thomas recently assisted a woman who lives in Louisville and operates an Airbnb property near a school in Cincinnati. She unknowingly rented the space to two sex offenders, and they were residing too close to the school. Police officers discovered their violation and told them to leave. Her question was whether to wait for the police to follow up or to file a case herself to have them removed.

“There’s a whole bunch of issues that can get the public tangled up,” Thomas said.

Thomas supplied information about the process for filing her case, but the decision on which route to pursue was the property owner's.

Lawyers Listen and Identify Options

In Darrilyn’s case, the municipal court noted on its docket in early April that it set an August trial date. That confused not only Darrilyn, but also Wall. He questioned why there was no response to Darrilyn’s motion. Knowing the courthouse as he does, he walked over to the staff in the court clerk’s office to ask.

After the clerk’s office checked into the matter, the case docket was updated. The court agreed to set aside the default judgment and re-open the case. Wall and volunteer attorney Gary Yerke, who spent his career in the financial industry, dug deeper into Darrilyn’s situation, which involved five tax years. A lawyer was representing the city. Darrilyn recently called the city and told them she wanted to pay, but the city said the matter was out of its hands. Wall explained that she instead should contact the city attorney’s office to discuss a settlement given that she was pursuing the case in court.

“But they want $11,000. I’m not OK with that,” she said. “I don’t understand how it got to this point. In the past, we went to court, paid, and then we were done.”

Wall and Yerke pored over documents, advised her to sort out the numbers, and gave her ideas for a resolution. After clarifying a few details, Darrilyn gathered her papers.

“Thank you,” she said. “You guys are so helpful.”

Without the center’s help, Darrilyn never may have discerned that the court hadn’t responded to her motion, been able to re-open her case, or figured out a direction toward a resolution.

“Win or lose, people just want a chance,” Wall said. “It’s the difference between losing overall and losing because you didn’t understand the courts and the processes.”

“People feel empowered, listened to, that they matter,” Pureval adds.

Key Ingredients for Successful Help Centers

Other courts interested in giving help to self-represented litigants have contacted Southers and Wall and visited their centers to learn about their structures and operations. Montgomery County Municipal Court, Cuyahoga County Municipal Court, and Franklin County Probate Court are among them.

It’s a reminder of the depth of the need. Civil legal disputes are handled in more than 15,000 courts across the country, and the courts estimate that 75 percent or more of their cases include at least one self-represented litigant.

Wall, Southers, and Pureval offer tips for courts considering a help center.

Location, location, location. “Find a space that works,” Southers recommends. “It should be visible, and easy for the public to access.”

The Franklin County help center’s first home was on the 10th floor of the building next to the municipal court. Southers said they saw only two or three visitors a day. He seized an opportunity when space on the court’s sixth floor became available. Since February of last year, people can take a quick elevator ride to that location from the many floors where their cases are handled. The numbers speak to the change: The center averaged 32 visitors each day in the first quarter of this year.

Figure out funding. Pureval focused on finding ways to save money when he took office. He said he succeeded in saving more than $1 million. Those funds were critical to making his idea for a help center a reality.

“Fund your priorities,” he said.

Southers said the municipal court judges in Franklin County allotted $1 of the court costs in each case to support the center. Edwards is paid through the court’s fund, and the city of Columbus includes Southers’ salary in its budget.

“Make sure you have funding for at least one attorney,” he said.

Identify partnerships and collaborate. The Hamilton County center is a partnership between the Hamilton County Clerk of Courts, Hamilton County Municipal Court, Hamilton County Board of Commissioners, and University of Cincinnati College of Law.

“It really was a community-wide effort,” notes Pureval.

The center, which was honored last year with the Justice Achievement Award from the National Association of Court Management, also identifies ways to avoid duplicating assistance that other organizations already are providing. When asked about sealing or expunging a case record, the staff directs people to the Hamilton County Public Defender’s Office, which guides people through this process.

“We work together, and refer to each other,” Wall said. “The justice gap requires a legal ecosystem to offer enough options.”

Be creative. Off on one side of the Franklin County center is a play area for children donated by a group within the Columbus Bar Foundation. To keep little ones entertained, it’s sprinkled with toys – many donated by court staff – and books, which grew substantially in number after gifts made by staff in the city prosecutor’s office.

Across the room are a couple of computers. Southers was able to obtain them from a Dayton-area middle school, where his father is the principal, because the school was disposing of them. A handy rack holding social services information was retrieved from the side of the street.

Adapt to public needs. One of the first law school fellows who staffed the Franklin County center mapped the times when each part of the court was busiest. The staff could predict what types of questions they were likely to receive at different times of day, and they set the center’s hours based on the information, Southers said. For example, they receive numerous questions about housing before and after the morning eviction court sessions.

“Identify the needs unique to your community,” said Pureval.

Turn to judges, magistrates, and court staff for ideas. A magistrate in Franklin County told Southers that individuals subject to wage garnishment because of a debt often are too late in challenging the action, so they developed a plan. As of a few weeks ago, the clerk’s office now refers all people with garnishment cases to the help center so they can learn the steps involved if they want to contest the underlying debt.

Go to the community. Southers links up with libraries and attends festivals to raise awareness about the center and to start the paperwork rolling off-site. He’ll also be talking in the community in the coming months as part of a grant to address racial disparities within municipal courts.

Be aware that visitors will tell others. After receiving helpful guidance, a hair stylist asked for information about the Franklin County center to post on Facebook. Southers notes they have a surprising number of visitors who mention they were referred by the hair stylist. It’s one of the unexpected ways word of the centers spreads.

Help Center Assistance Opens Doors to Greater Justice

Even with thousands of people flowing through their doors each year, the staffs in both counties know they’re just beginning to tap into the public’s need for guidance in civil cases. They hope to address demand for social services, expand outreach, and, most of all, see people earlier in the legal process.

Southers notes that help centers have minimized problematic situations from filings made on napkins to delays in resolving cases. The centers are demonstrating with data greater efficiency and cost-savings for the courts.

“They help the dockets move more efficiently,” Pureval said. “Courts can focus on the business at hand, rather than answering basic process questions.”

Chief Justice O’Connor agrees.

“With knowledgeable help center staff, the public will slash the time it takes to address legal problems,” the chief justice said. “That can mean avoiding time off from work, the loss of wages, or even the loss of a job.”

The efforts to broaden access to justice for more people has an added benefit of building positive connections between the courts and the communities they serve.

“When it comes to administering justice, there is no substitute for human intervention, human understanding, and human compassion,” she said.

CREDITS: