Youth Diversions

For young people in trouble, Ohio courts offer constructive alternatives to the juvenile and criminal justice systems with a blend of education, accountability, support, and problem-solving.

About 15 percent of teens have shared a sexually explicit text message, image, or video electronically – known as sexting – and 27 percent have received them, a 2018 study found. Under child pornography laws in many states, juveniles can be convicted for creating, disseminating, or viewing such materials, even when they take and share an image of themselves.

State legislatures have grappled with whether, and how, to distinguish sexting by youth from the exploitation of minors through child pornography. In Ohio, a child pornography conviction for a juvenile of a certain age could lead to designation as a sex offender, which carries weighty consequences, such as required registration with authorities at least every year. It has left juvenile courts in the state sorting out what to do with young people caught in these predicaments.

At the Mahoning County Juvenile Court, staff thought youth and parents needed a better understanding of these laws. They started calling schools to set up visits with students to talk about the risks, including the legal ones, of sexting.

“The laws make juveniles sexual predators if they are involved in sexting,” said Judge Theresa Dellick. “We needed to do something to educate our youth to keep them out of court.”

In September 2015, the efforts were formalized into the court’s Cyber and Relational Diversion Program (C.A.R.D.), a partnership with the county prosecutor’s office that focuses on proactively informing youth about the personal and legal consequences of sexting, as well as cyber-bullying and sexual harassment.

C.A.R.D. was one of several initiatives recognized by the Ohio Supreme Court in the last year for diverting juveniles from the courts and into programs that try to address the array of issues in a child’s life that may steer them toward trouble. Because juvenile courts focus on rehabilitation rather than punishment and detention, “diversion” programs are key. With diversion programs, which tend to deal with youth involved in lesser offenses such as trespassing, shoplifting, unruliness, and truancy, courts direct youth away from the formal juvenile justice system and toward alternative options.

The five-week Mahoning County program, designated by the Supreme Court as a “promising practice,” requires the involvement of both the youth, ages 12 to 17, and the parents. It relies on referrals, which arrive from many corners, including law enforcement, counselors, teachers, and parents. Judge Dellick said evidence indicates that intervention with these issues in early adolescence is critical and parents must be involved to ensure long-lasting behavioral changes for the child and the family.

The weekly sessions in C.A.R.D. cover:

- Education about types of bullying, sexual harassment, and appropriate and inappropriate behavior

- Steps to take when bullying, sexting, and sexual harassment happens

- Possible charges against a juvenile and the child’s parents for the actions

- Potential legal consequences, such as probation or ankle monitors at the lesser end

- Descriptions of healthy relationships, and the importance of self-esteem and self-worth.

When parents and students first hear about the ramifications of these behaviors, a hush often descends across the room, Judge Dellick said. Then, there typically are a lot of questions and requests for advice.

Since 2015, more than 100 youths have completed the C.A.R.D. program. Only two juveniles were charged for their actions, Judge Dellick notes. Court staff continues to visit schools, educating about 750 students annually, she said.

Diversion Favored for Juveniles

Diverting youth from the juvenile and criminal justice systems isn’t new. In 1967, a presidential commission called for alternatives to court for juvenile offenders. Ohio adopted a rule for juvenile court proceedings (Juv.R. 9), effective in 1972, that states, “In all appropriate cases formal court action should be avoided and other community resources utilized to ameliorate situations brought to the attention of the court.”

Today, Ohio’s juvenile courts implement an assortment of diversion programs for youth. And they continue to gather information about what works and what doesn’t and to innovate, developing new strategies with the knowledge gained over the years.

Judges Sandra Stabile Harwood and Samuel Bluedorn of the Trumbull County Common Pleas Court have developed several programs for youth in its family court division, and four earned recent accolades from the Supreme Court. Court administrator Stacy Ziska said the court’s diversion department screens all youth to identify those eligible for any of the court’s programs. During their interactions, staff noticed that girls in contact with the court have some unique needs. To provide a safe space for them to have a voice and feel heard, the court formed Girls Circle in 2013, Ziska said.

The support group, which follows curriculum from the national nonprofit One Circle Foundation, addresses issues girls face, such as body image, voicing feelings, female friendship, and healthy sexuality. Ziska said setting life goals and learning about positive relationships are central components.

The Girls Circle focus on defining and establishing healthy relationships resonated with Judge Stabile Harwood, who joined the family court the year the initiative began. During her four terms as a state legislator, Judge Stabile Harwood worked on a teen dating-violence bill and found that many girls didn’t understand what a healthy relationship looked like, she said.

“The Girls Circle program has been able to provide an environment for the girls to feel confident to express their thoughts in a judgement-free zone,” Judge Stabile Harwood said.

The benefits of the approach are borne out by research. Studies have shown that the gender-specific model not only reduces recidivism, alcohol use, and self-harm, but also improves body image and self-reliance and increases social connections and commitment to school.

Girls Circle participants in Trumbull County – four to six girls in each group – meet for eight to 10 sessions, usually once a month. Projects, such as designing journal covers or crafting blankets to donate to others, foster an environment that facilitates conversations, Ziska notes.

Among the feedback, girls report that they learn they aren’t alone in the situations they encounter, Ziska said. Of the 60 girls who have participated to date, only four were adjudicated for a new offense within six months after completing the program, according to court records. This year, the court adopted a program from the same foundation for boys.

Family Focus Essential to Success in Many Cases

The Trumbull County court staff also works with families, not just individual juveniles. The court identifies youths whose family dynamics may play a role in their behavioral struggles and offers family counseling. The counseling sessions take place in the family’s home or their community, rather than within the formal setting of the courthouse.

“Our Multi-Systemic Therapy Program is the first time capturing a lot of parents who never learned the tools to address issues any differently,” Judge Stabile Harwood said. “It engages the whole family.”

Other courts dealing with juveniles in trouble find it essential to involve family members in substantive ways as well. The Coshocton County Probate and Juvenile Court’s youth diversion program, overseen by Judge Van Blanchard II, is multi-layered and starts with a course called “Nurturing Parent.”

Court administrator Doug Schonauer said the two-week, four-hour course, based on a national curriculum designed in part to reduce delinquency, is geared toward improving parent-and-child communication with a focus on teen issues and brain development.

The family signs a contract to participate in the court’s voluntary diversion program, which also incorporates drug and alcohol screenings, homework and school attendance requirements, and eight hours of community service, said Schonauer. For community service, participants may assist churches or local nonprofits, or assist at one of the county’s well-known events, such as the Chocolate Extravaganza or Taste of Coshocton. Mentioning the kids’ enthusiasm sampling foods at the Taste event that they’ve never had before, Schonauer said these activities are the first exposure some of them have to cultural events.

The court is particularly observant, though, of how youths in the program adjust to school expectations.

“Education is our barometer,” Schonauer said. “We relate school success to overall success.”

While highly engaged youth and families might complete their contract in about 90 days, the program more typically is completed in five or six months, he said. Once finished, the court notifies the juvenile that the legal complaint won’t be filed with the court, no court hearing will occur, and the youth will have no record.

The Coshocton County Juvenile Court, and numerous juvenile courts statewide, collect data about the number of youths participating in these types of programs, along with youth demographics, types of offenses, sources of referrals, and outcomes. The data can help to secure funding from the Ohio Department of Youth Services RECLAIM initiative (Reasoned and Equitable Community and Local Alternatives to the Incarceration of Minors). Last month, about 30 juveniles took part in the Coshocton County court’s diversion program, Schonauer said.

Designing Diversion Based on Each Youth’s Circumstances

Years ago, the diversion program for juveniles in Delaware County Juvenile Court was roughly 90 days across the board, regardless of the mistake or offense, said Eddie Parker, diversion coordinator. Parker, who started working at the court in 2000 and has assisted with juvenile diversion efforts for the last 10 years, thought the one-size-fits-all approach lacked evidence for its effectiveness. Inspired by courts in Michigan and Alaska, he wanted to try creative solutions tailored to each child.

“How can we be a change agent for these kids?” he asked.

In one case, a 17-year-old caught with other teens drinking at a party arrived in the diversion program. Parker did a risk assessment, which came back low, indicating that “this was not a problem kid,” he said.

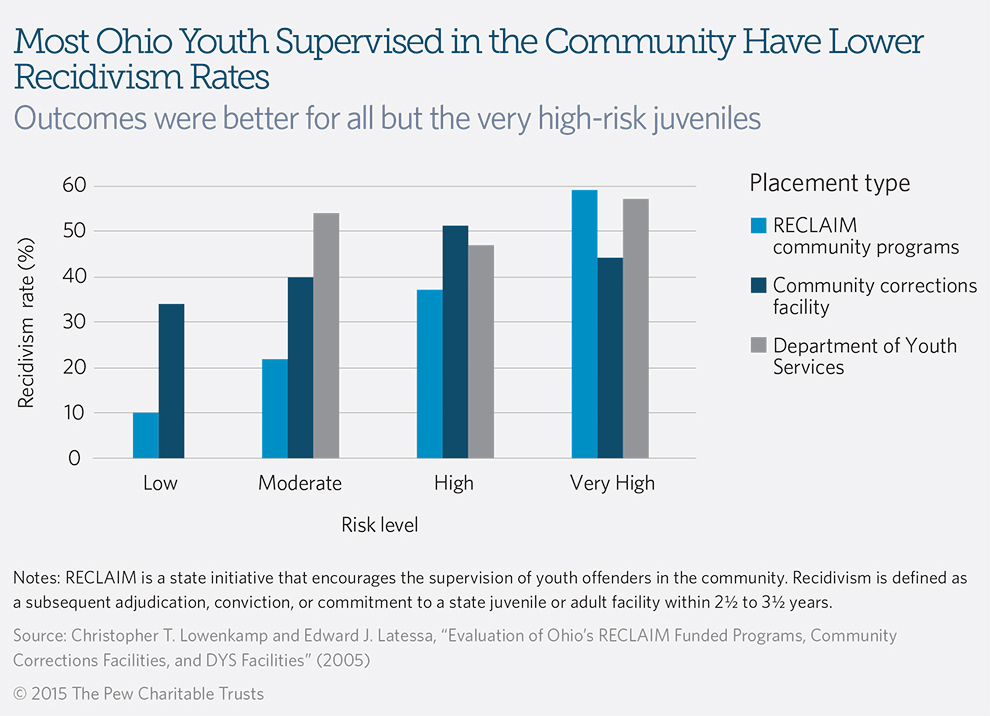

A Pew Charitable Trust report about juvenile incarceration incorporates a 2005 study of Ohio’s RECLAIM program, which found that low- and moderate-risk juveniles held in facilities were at least twice as likely to reoffend as youths under supervision or in community programs.

But, Parker recalls, the youth was “despondent” because her father recently died. When the school was informed the student had been drinking illegally, it suspended her from the sports team she loved. Parker put her in the court’s “fast-track diversion,” which lasts approximately 30 days.

After conducting a thorough interview, he determined that her family’s regard was important to her, so he had her write a letter about the negative effects of her actions on them. He also thought it was essential for her to find another activity she felt passionate about, given that she couldn’t play on her team. She chose to volunteer at a pet shelter. In Parker’s opinion, random community-service tasks don’t motivate youth to change, so he made sure her work was tied to something she cared about. A few years later, the young woman graduated second in her class at Ohio State University.

At the other end of the spectrum are juveniles who require more intensive approaches. Parker worked with a teen who had a $200-per-week drug habit and was holding drug parties at his house during the frequent times his parents were out of town. But the youth was functional – going to school and working.

After determining the teen was at high risk for continuing to get into trouble and likely landing in court, Parker identified consequences that would be significant to this youth. Coordinating with the parents, Parker took the teen’s cell phone and his driver’s license and placed him under house arrest until he tested clean of the drugs. The young man and Parker also agreed on a unique type of restitution to his parents, taking money that he would’ve used to buy drugs and paying it to his parents, Parker notes. The idea was to place a higher value on his parents than the drugs. It worked. Parker said the parents later sent him a letter saying they have a different kid who talks and listens to them.

The Delaware County court, led by juvenile/probate Judge David Hejmanowski, touts an impressive record of success. More than 98 percent of the 132 youths in the diversion program in 2018 successfully completed their requirements, Parker reports. It was one of seven that received the Supreme Court’s highest distinction as an evidence-based practice.

“I want to get to the root of the problem,” he explains. “And doing it the right way is cost-efficient. It doesn’t burden the courts. It just makes great sense.”

“In Delaware County, we are particularly proud of several innovative practices that we believe improve outcomes for youth,” Judge Hejmanowski said. “Diversion gives young men and women to opportunity to demonstrate to the court that their minor offenses were anathema to their character, rather than reflective of it. Through diversion they can learn from their mistakes; participate in education, counseling, and treatment; complete community service; and maintain a clean record.”

Courts Work toward Constructive Outcomes

Heading west to the Madison County Juvenile Court, Judge Christopher Brown and diversion coordinator Alyssa Edley run a program called I.M.P.A.C.T., Imagine Making Positive Accountable Changes Together. Started in January 2017, the initiative is centered on family conferences with Edley that encompass counseling, volunteering, and education. Court records show I.M.P.A.C.T. helped 108 kids and 91 families in its first two years.

These examples illustrate a few of the concerted diversion efforts by juvenile courts across the state. It’s a challenging endeavor at times for courts because of their stretched resources and deep reliance on their community partners in these programs. However, the courts aspire to help as many youths as possible avoid acquiring a court record that might taint the rest of their childhood, and even their adult lives. They also hope to empower juveniles to come to terms with their personal and family challenges and to re-direct themselves to a more productive path.

“Now they’re aware of resources and know who and where to ask for help,” Coshocton’s Shonauer explains. “Anything we can do to have them leave in a better place than they came in is a positive.”

CREDITS: