Partners in Justice

Magistrates accept pleas, handle hearings, conduct jury trials, and author decisions in courts throughout the state. Working with the judges who assign them to perform these duties, Ohio’s magistrates have become integral to the operation of the state’s justice system.

The number of cases they handle can be hefty, and their days can be hard to predict. But Ohio’s magistrates convey a commitment to their courts and to their work, even when the volume sounds daunting.

On a recent Wednesday in Franklin County Municipal Court, Magistrate David Jump had 300 traffic cases scheduled, and 120 people appeared in court.

Some days in Montgomery County Juvenile Court, Magistrate Greg Scott said he’ll oversee 20-plus cases in the morning, and as many in the afternoon. Magistrate Michelle Edgar is likely to hear eight to 12 cases daily in the Fairfield County Juvenile and Probate Court.

When Cuyahoga County Domestic Relations Judge Diane M. Palos was a magistrate, she handled temporary child support hearings. Judge Palos served as a magistrate – then called referees – for more than 20 years before she was appointed, and then elected in 2010, as a judge in the same court. In the 1980s, she said, 18 daily hearings were standard.

Patricia Hider, a Butler County Probate Court magistrate, described how her morning starts with a plan. Before court begins, she and her bailiff review the docket, talking through every case file. And then?

“Then we strap on our roller skates and get prepared for the unexpected,” she said.

People have had emotional meltdowns in the courthouse rotunda. Or, eight or nine family members will show up unexpectedly for a case, said Hider, who works on such issues as contested guardianships, name changes, and adult neglect and abuse cases. Those entering the courtroom typically haven’t done anything bad, she said. Instead, the people she sees regularly are family members who can’t make medical decisions and are trying to make their way through the process. Empathy is essential for helping the people who appear in court, Hider noted.

“If they were able to solve their own problems, they wouldn’t be in front of stranger,” she explained.

Magistrates' Roles

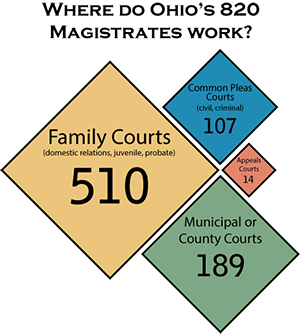

The number of cases winding through some Ohio courts makes magistrates vital to an efficient justice system. As of August, the state had 820 magistrates. It’s a number that fluctuates because court rules allow individual judges to determine whether they need magistrates and how many.

Over a few decades, the Ohio Supreme Court has broadened the responsibilities and authority of magistrates, who were called referees until 1995. Magistrates are judicial officers who, rather than being elected like judges, are appointed by a specific judge. A magistrate must be an attorney with four years’ experience practicing law and in good standing with the Ohio Supreme Court.

Within state courts, 62 percent of magistrates work in domestic relations, probate, and/or juvenile courts. Nearly 200 staff municipal or county courtrooms, and about 100 are appointed to civil and criminal cases in common pleas courts. They hold hearings and write decisions. In criminal matters, magistrates handle arraignments and preliminary hearings. With misdemeanors, they can accept guilty and no-contest pleas, recommend sentences, issue temporary protection orders, and hear certain non-jury cases. In civil lawsuits, they can conduct jury trials if the involved parties approve.

Essentially, magistrates can do nearly anything judges can. However, magistrate rulings are subject to review by the judge assigned to every case.

On Justice's Frontlines

Practically speaking, particularly in trial courts, the public is likely to encounter a magistrate.

“You are the face of the public official – the one many members of the public in the courts see,” Hider explained. “Much of the public opinion of the court is formed by the magistrates.”

“Especially in big courts, such as Franklin County, I don’t think judges alone could handle the volume of cases,” Jump noted. “The backlog would be overwhelming; the delay, tremendous.”

Franklin County Municipal Court has 15 judges and five full-time magistrates. Along with a pileup of traffic cases, Jump and the other magistrates juggle small claims cases, evictions, collection matters, and misdemeanors. Contract disputes and personal-injury jury trials are typical for Jump, who’s been a municipal court magistrate for 22 years.

Judge Palos said the domestic relations docket in Cuyahoga County is too vast for the five judges to process all the cases without assistance from their 19 magistrates. Each one is given a distinct responsibility – either trials, motions, spousal and child support, or domestic violence.

“Magistrates are a benefit to the public,” Judge Palos said. “They cost less than judges, and they’re effective for moving cases through the system.”

“We’re helping to keep the wheels of justice turning,” Edgar added.

The Fairfield County Juvenile and Probate Court has two magistrates, and Judge Terre Vandervoort also acts as the clerk of court.

“She has so many administrative responsibilities, it’s almost impossible for her to hear every juvenile court case and complete those administrative duties as well,” Edgar pointed out. “With magistrates, cases move into and are resolved by the court more quickly.”

In jurisdictions where the number of initial case filings are declining, Scott noted that the length of time some cases remain in the justice system can be unpredictable, requiring the attention of court staff in ongoing ways. For example, the quantity of motions filed within individual cases is climbing, he said.

“And, in a custody dispute involving a 2-year-old, we may see that one case return repeatedly for the next 16 years,” he explained.

Backgrounds and Temperaments that Fit

Along with describing their crucial role in the administration of justice, the magistrates also highlight the compelling nature of the work and how it suits their personalities.

Jump started out with the municipal court, working there while in law school and for a few years after. Then, as a general practice lawyer for 11 years, he handled misdemeanors and domestic relations cases. But he decided to return to the court as a magistrate.

“I really enjoy being the neutral rather than the advocate,” Jump said.

Judge Palos agreed. She has served continuously on the bench as either a magistrate or a judge since 1986.

“As a magistrate, and now as a judge, I get to be impartial,” she said. “I’m better in the middle than as an advocate because I know there are more than two sides to every story.”

While she may not miss being called “your magistry,” she said being a magistrate, and a judge, speaks to her strengths – negotiating conflicts, finding positive resolutions, and doing what’s right.

Hider left a career in biotechnology and turned away from training for the 2004 Olympic team in recurve archery to fill a magistrate opening in 2003. She enjoys the intellectual rigor.

Something as seemingly innocuous as a name change can require careful legal consideration. She mentioned, for example, that the number of requests from transgender youth who want to change their names is rising, and there’s little law directly addressing the issue. Her boss – Judge Randy T. Rogers – stresses that the lack of precedent doesn’t give license to make up a solution, Hider noted. The judge encourages a scholarly approach using “legal reasoning by analogy” to ground a ruling on a similar area of law. It enables her to follow his motto: “Do the right thing the right way.”

Edgar spent more than a decade in private practice, accepting juvenile and domestic relations cases, working as a guardian ad litem (GAL), and taking assignments as a court-appointed lawyer. That breadth of experience as an attorney in the court led Judge Vandervoort to ask Edgar to join the court as a magistrate addressing similar cases.

Edgar said the variety of the work is one aspect she likes. She shares her dedication beyond the courtroom by serving on Ohio Supreme Court committees and teaching a GAL course for the Court’s Judicial College. She is drawn to being a part of making changes to the legal system for the better and identifying best practices for the future, she said.

In Montgomery County, Scott embraces working with individuals. His parents owned a butcher shop and carryout in Kettering, and he discovered he liked interacting with people one on one. As a lawyer, he assisted clients with criminal, probate, medical malpractice, and domestic relations issues, and he was appointed to help juveniles as a GAL or as their attorney.

“We’re concerned about those before us, and we take their lives very seriously. We work hard to treat them as the individuals they are.”

During 23 years as a magistrate, Scott, who’s retiring at the end of the year, found he could combine his love of the law with putting into practice what he saw over the years watching judges he respected.

“These judges treated each individual in front of them like they were the most important person in the room,” Scott said.

Dealing with Human Struggles

Some days are challenging, though.

“There’s a sadness sometimes for folks’ situations,” Scott said. “It doesn’t excuse criminal or unruly behavior, but they didn’t choose the circumstances of their birth. Some didn’t have the opportunities that I and others working at the court have had, and many youth are without the capacity to address their issues.”

Edgar added: “We’re considering the best interests of the child, but these are often family issues rather than just the actions of one youth. Sometimes we’re telling people how to parent. It’s frustrating when we see families repeatedly or the county’s limited resources aren’t getting to them.”

Jump also pointed out that it’s distressing to inform people they lost or to give them bad news. Eviction cases came to his mind.

“It’s tough telling people who are experiencing difficult times that they have to leave their home,” he said. “But we’re proud of the array of services, such as mediation, we offer in Franklin County to protect the rights of both sides and to try to avoid ever getting to that point.”

Hoping People Can Move Ahead

Among the array of reasons the magistrates love their profession, making a difference with the families and individuals who enter their courtrooms rises above all else.

“When there are frustrations, it makes me push to keep trying,” Edgar said. “I like helping families to move away from the court and forward in their lives.”

“Any one of us might be in the situations I deal with in municipal court,” Jump said. “I like being able to help people through those difficulties.”

Scott also expressed the importance of showing compassion to the youth and families who appear in court.

“We’re concerned about those before us, and we take their lives very seriously. We work hard to treat them as the individuals they are,” he said.

For Hider, an adult abuse case she heard demonstrates the impact magistrates can have in a person’s life. A woman was living with her sister, who locked the woman in her room, didn’t give her access to a bathroom, and beat her. Hider issued an emergency order to remove the woman from the dangerous environment.

“With the cases I hear, I don’t have to wonder if I’m helping people,” Hider said.

Careers Reflecting Diligence

These dedicated magistrates have given decades of public service to their profession, and they work hard to understand the often complex laws the public needs to navigate. It’s an investment they hope serves people across the state as well as the legal community.

“Magistrates can focus in and be experts in specific legal areas, which is a big help for judges,” Judge Palos said. “Courts need more than one person to think about these issues. It’s a powerful thing that produces better results for the public.”

“We’re an extra set of eyes, often bringing career-long expertise to cases,” Jump noted. “It adds to the quality of the work of the judiciary.”