Righting Wrongful Convictions

The integrity of criminal convictions and postconviction procedures is a subject under increased scrutiny as criminal justice reform efforts blossom nationwide. In Ohio, a task force has been charged with seeking strategies to combat wrongful convictions and recommending reforms.

There have been many high-profile exonerations nationally: Walter McMillian. The Central Park Five. To name only two cases. The list of the exonerated in Ohio also is long and includes Rickey Jackson, Glenn Tinney, Joseph R. Fears Jr., Evin King, and 81 others. Wrongful convictions point uncomfortably to unsightly cracks in our criminal justice system. As more continue to come to light, states are examining their processes that at times fail to take accountability for – and to fix – the errors that cost people their livelihoods and their freedom.

“Everybody who is a stakeholder in the criminal justice system has got to recognize that we make mistakes,” said Patricia Cummings, the prosecutor who heads the conviction integrity unit in the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office. “And, on top of that, we’ve got to recognize that we all have an obligation to take the steps necessary to remedy those mistakes.”

Cummings spoke at a meeting of an Ohio task force charged with identifying steps to address wrongful convictions. The task force, which Ohio Supreme Court Chief Justice Maureen O’Connor convened last year, is investigating ways to ensure the integrity of convictions in the state and to improve the routes available after a conviction to review innocence claims based on issues such as bad forensics, misconduct by police or prosecutors, false accusations, false confessions, and mistaken eyewitness identifications.

Among its duties, the task force is looking at approaches taken by other states, including conviction integrity units, innocence commissions, and postconviction review processes.

“We’re not breaking new ground,” Sixth District Court of Appeals Judge Gene Zmuda, who chairs the task force, told Court News Ohio. “It’s a growing trend that there are more opportunities for individuals to prove their innocence. Our judicial system does not tolerate, and should not tolerate, wrongful convictions.”

Task force members are hearing from officials nationwide who have taken varied tacks in response to vocal concerns about wrongful convictions. That’s what brought Cummings and her boss, District Attorney Larry Krasner, to one of the group’s meetings held by videoconference.

Philadelphia D.A. Revamps Conviction Review Process

When he began the job in early 2018, Krasner bolstered the conviction review unit already existing in the D.A.’s office. Questioning whether a longtime prosecutor running the unit could impartially investigate the work of other prosecutors, Krasner hired Cummings, who had led the conviction integrity unit in Dallas County after working initially as a juvenile prosecutor and then as a defense lawyer. Cummings pushed successfully for a law in Texas requiring prosecutors to open files to defendants and to keep records of the evidence disclosed.

Krasner, who spent his legal career on the defense side, is one of dozens of prosecutors across the United States making criminal justice reforms central to their leadership. Conviction integrity units are one strategy aimed at reform.

“It is not a fluke, it is not an anomaly,” Krasner said of the climbing number of reform-minded prosecutors. “There is a genuine appetite among voters – it’s not all by party lines, there’s quite a bit of conservative support – for modern approaches to criminal justice and prosecution.”

Reasons Identified for Wrongful Convictions

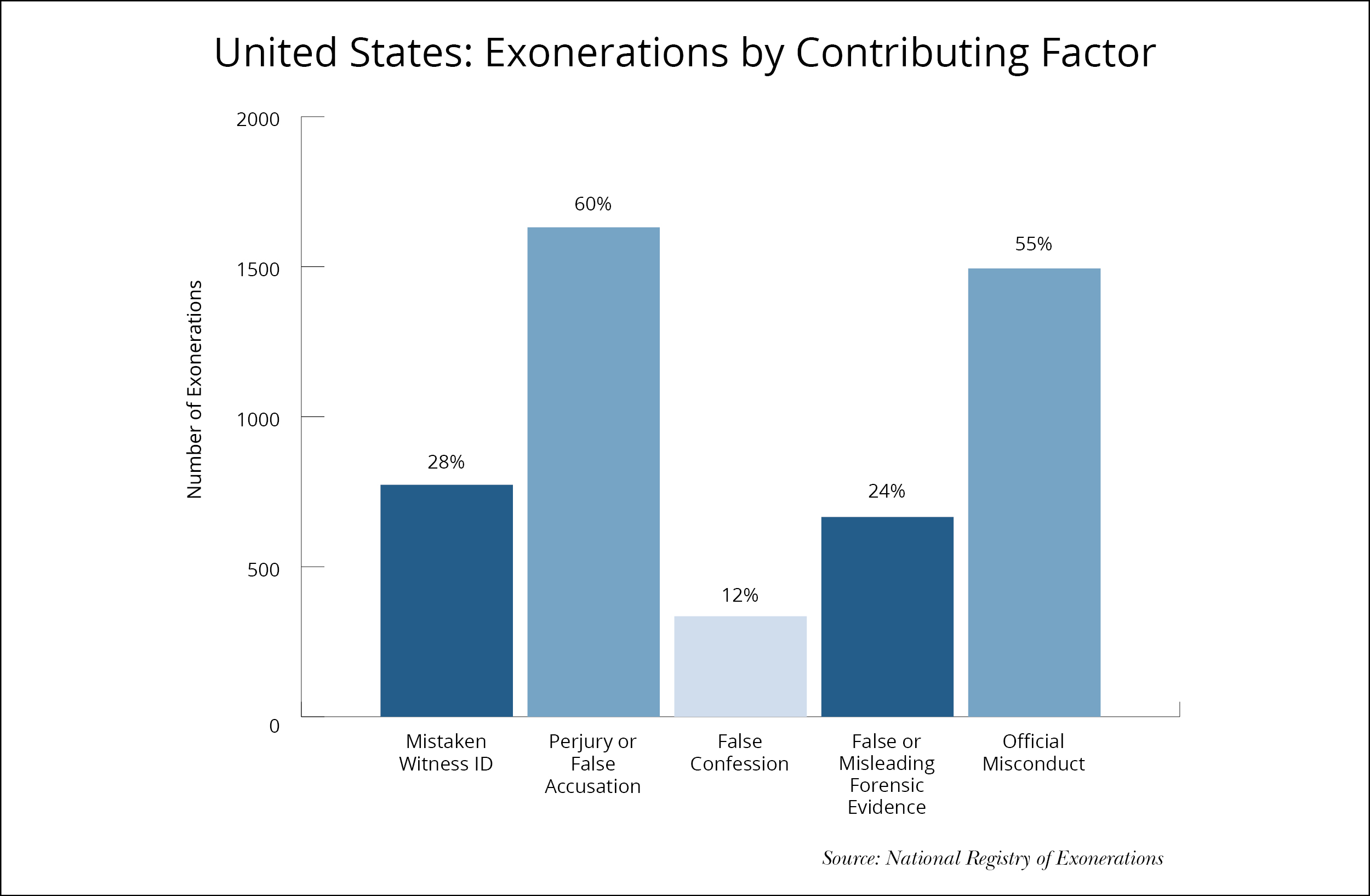

Why are people wrongfully convicted? According to the National Registry of Exonerations, leading causes are one or, more typically, a cluster of these factors: perjury or false accusations by others (60%), official misconduct (55%), wrong eyewitness identifications (28%), false or misleading forensic evidence (24%), or false confessions (12%). Wrongful convictions have grave ramifications for several dozen people on average each year: The National Registry has tracked 2,749 wrongful convictions in the United States since 1989.

Most wrongful convictions identified early on were revealed by DNA evidence proving the person convicted didn't commit the crime. Cummings noted that wrongful convictions that were overturned based on DNA have expanded the conversation regarding exonerations in recent years. In DNA-based exonerations in New York, for example, 40 of 356 exonerations were individuals who pled guilty. DNA exoneration data are fueling a discussion to not ignore other concerning cases that lack DNA evidence, including those in which defendants pled guilty, Cummings said.

She also pointed out that the defendant isn’t the only one harmed when the wrong person is found guilty of a crime.

“When these wrongful convictions occur, the damage to our criminal justice system and to our country is widespread,” she explained. “So often you hear the focus is on the damage to the defendant. But everybody has to pause and think about the damage that also occurs to the victim and that occurs to the system as a whole.”

She said victims have to re-live the crime again when they learn evidence is showing the real perpetrator was someone other than the person convicted. In addition, victims become distrustful of the system that they relied on to bring them justice, Cummings stated. The harm to victims caused by wrongful convictions can serve as a motivating driver for groups working to get it right, she said.

Conviction Integrity Units Built on These Basics

Historically, defense attorneys and innocence projects have carried the burden of seeking to overturn wrongful convictions. While they do a good job, they don’t have nearly enough employees or funding to overcome this problem, Cummings said. Access to evidence and resources for testing it are an additional hurdle for outside groups. Conviction integrity units (CIUs) add another tool to pry into these potential injustices.

CIUs are typically established in local prosecutor or district attorney offices, although a few states are experimenting with statewide units. Some CIUs are given robust resources, while others function on slender means. For staffing, though, Cummings suggested at least two prosecutors, one investigator, and a paralegal.

Krasner added that CIUs need attorneys who can be independent, not swayed by relationships with other divisions of the prosecutor’s office, and who offer a wide breadth of criminal trial work – specifically with death penalty, homicide, and felony cases. That experience fosters insights.

“They can spot the wrinkle. They can see the nuance in the transcript. They can wonder why a thing is not there in the file,” Krasner said.

Then, Cummings said, it’s crucial to get creative.

Look for grant money from the government, foundations, and academia, she recommended. Citing an example of a university professor who worked at no charge for the Philadelphia unit, Cummings and Krasner both emphasized asking others for help even if you have no money. As the CIU staff shows they are committed to the work, the unit will grow over time, Cummings added.

Unit’s Placement in Prosecutor’s Office Is Pivotal

She also stressed the positioning of CIUs within a prosecutor office’s hierarchy as key. In Philadelphia, Cummings reports directly to Krasner. Two to four CIU assistant district attorneys are assigned to each case under review. They vet the cases, debate them with each other, and consult with outside experts as needed. Then she takes a list of cases the team believes they should pursue to Krasner, and the two discuss.

Pressing the importance of a unit’s independence, she advocates for reporting directly to the prosecutor.

“You will not be popular in the prosecutor’s office,” she said. “You must have support from the top.”

She described a shift in the Texas office structure that affected the CIU’s work. In Dallas, the CIU initially was placed above the postconviction appellate group, which defends convictions. The unit garnered support from district attorneys across party lines. But a subsequent district attorney who supported the unit adjusted the hierarchy in the prosecutor’s office. The DA placed the CIU and the postconviction appellate team on the same level. Cummings said exonerations declined because the postconviction prosecutors had a seat at the table in deciding whether the CIU should pursue relief for a defendant. They opposed some cases that the CIU had determined were worthy to pursue. She called it a lesson learned.

The Ohio Innocence Project’s Director Mark Godsey told Court News Ohio that he supports conviction integrity units, but echoed Cummings’ cautions regarding their structure.

“If set up properly, with the required political insulation and independence, they can work far better than any innocence project. Some of them work that way, and it’s an amazing thing to see in action,” Godsey stated. “The problem is that most of them don’t work properly, because they have not been set up in a way to fight confirmation bias and tunnel vision, and they don’t have the necessary insulation from internal pressure coming from other prosecutors.”

Cummings also noted that conviction integrity units in some counties across the country have boards. That’s the setup in the Cuyahoga County Prosecutor’s Office, which is one of three conviction review units in Ohio.

Cummings doesn’t believe, though, that any extra layers between the elected prosecutor and the CIUs are necessary.

Statewide Conviction Integrity Offices Considered

New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Michigan formed conviction integrity units at a statewide level, in their respective state attorney general’s offices. The jury is still out on these because they are so new, Cummings stated. In Pennsylvania, she noted, the attorney general must wait for local elected officials to agree to send a case to the state CIU before the team can begin reviewing a case. This makes it difficult for the unit to identify cases on its own and to remedy wrongful convictions, she said.

The National Registry of Exonerations identifies 80 conviction integrity units working at the local or state level within state and federal court systems. Cummings argued that local CIUs are finding the most success. While some units are viewed as “conviction review in name only,” or CRINOs, she noted that the Philadelphia unit exonerated 15 people in three years, from 2018 to 2020.

Lest someone thinks the prison doors have been swung open for everyone, Krasner countered that he and the Philadelphia CIU have supported exoneration in only 4 percent of the cases they have reviewed.

“We have rejected far more requests for exoneration than we have accepted,” he said.

Innocence Commission Formed in North Carolina

One critique of conviction integrity units is that prosecutors may not be the ideal choice for looking into challenges to convictions – because they pursued the convictions. Looking for an alternative, North Carolina implemented an innocence inquiry commission, an independent statewide group that started its work in 2007. The commission has reviewed about 2,900 claims in 15 years. It has held 17 hearings, and 15 people have been exonerated based on its work.

That’s significant, Cummings said, but she noted that the North Carolina legislature limited the commission’s scope to “credible claims of actual innocence.” That means the commission cannot address serious procedural flaws or sentencing inequities in the criminal cases. She said many cases in her office start as actual innocence claims, but if there’s not enough evidence to pursue that route initially, the CIU still can investigate other significant procedural allegations.

North Carolina’s commission also requires the defendant’s complete waiver of privilege before it will review a case. In Philadelphia, they require only a limited waiver, Cummings said. She doesn’t see the benefit of a full waiver with an actual innocence claim. Defendants sometimes say things that can be misinterpreted, but that doesn’t mean they were guilty of the crime, she explained. The limited waiver allows the CIU prosecutor to talk to the defendant or to look at the trial counsel’s file to see if the defense received all evidence from the prosecutor.

Overall, though, she strongly encouraged a broad mandate for reviewing possible wrongful convictions.

“What kind of funnel do you create in terms of the kinds of cases you look at? The wider the funnel, the better. The more narrow the funnel, the fewer people you’re going to be able to identify and set free because they’re innocent,” she said, citing research from the University of Pennsylvania Law School.

Ohio Counties Create Units for Conviction Review

The National Registry of Exonerations lists one CIU in Ohio – the Cuyahoga County Conviction Integrity Unit. Formed in 2014, the Cuyahoga County CIU today defines its mission as “to review legitimate claims of innocence or other compelling claims that warrant review (based upon compelling evidence that such review is necessary in the pursuit of truth and justice).” The CIU policies, which were restructured in July 2020, state that a person’s claim in Cuyahoga County must not be solely a legal issue that was previously raised or could have been raised at trial or during the appellate process. In addition, new and credible evidence of innocence must exist.

The CIU established a conviction integrity board as well as an independent review panel as part of its process. The CIU’s assistant prosecuting attorneys first evaluate applications and discuss them with the prosecutor, who decides whether or not the unit should conduct a full investigation.

Applications can be filed only after all state appeals and postconviction petitions are exhausted, and claims from applicants who pled guilty are evaluated “in rare and extraordinary circumstances,” the policy states.

After the CIU completes a full review of a case, the board and the panel separately review the findings and determine whether more investigation is needed or to send the claim to the prosecutor for consideration. The board is comprised of six appointed assistant prosecuting attorneys and one volunteer attorney or retired Cuyahoga County judge, and the panel has at least four members, including two lawyers and two community leaders.

The prosecutor then makes the call how to proceed. For approved applications, the CIU contacts the applicant or the applicant’s attorney to plan the filing of a motion with a court.

Since 2017, when the current prosecutor took office, the CIU has received 141 cases. Of those, three applicants have been exonerated and two exonerations are pending, the office stated. Five others have had their original convictions vacated and, where warranted, entered guilty pleas to lesser charges. All five were released from prison. In one additional case, the defendant was released from prison on judicial release.

Although not listed on the national registry, the Summit County Prosecutor’s Office established a conviction review unit (CRU) in 2019. It’s set up differently than Cuyahoga County's. The prosecutor’s chief counsel, who reviews claims, assigns those determined to be credible to prosecutors on staff as special assignments.

“The CRU’s work is important for public safety. If the wrong person is sitting in prison for a serious violent crime, the real perpetrator could still be at large. Further, unfair trials and wrongful convictions corrode public confidence in the justice system,” states the CRU’s policy.

Just this month, the Franklin County Prosecutor’s Office noted in a filing with the Ohio Supreme Court that it has created a conviction integrity unit.

Philadelphia Team Works to Cultivate Trust with Judges

Attendees at the task force meeting asked the Pennsylvania prosecutors about judges’ reception to motions to exonerate people. Krasner said a small number of judges were somewhat suspicious at first when prosecutors were agreeing about anything with defense counsel. As judges closely reviewed the cases, though, they saw the CIU wasn’t trying to exonerate everybody – in fact only a small percentage – and saw the “care and balance” and legal research the unit put into the cases it brought before the court, Krasner said. That led the skeptical judges to become more trusting of the integrity unit.

Cummings said they conduct a thorough investigation and briefing to lay out what happened, what new evidence they have, and why the person is entitled to relief.

“For conviction integrity work to be successful, it needs to collaborative, not adversarial. It is in everybody’s interest to identify the innocent, and so we should work together,” she said. “That is so foreign to so many judges because that’s not how the criminal justice system usually works. It’s not that we’re prosecutors behaving as defense lawyers, it’s that we’re collaborating with them to get accurate results and uphold our oath to do justice.”

Prosecutor Perspectives Vary on Specifics

Krasner commented on the tension between the concept of finality in the legal arena and a prosecutor’s promise to uphold justice.

“Some legal scholars and many traditional prosecutors emphasize finality – the importance of a conviction being final, with no further litigation allowed, forever,” Krasner said. “Finality and the prosecutor’s oath collide when crimes remain unsolved and when innocent people remain in jail.”

Last August, the Ohio Prosecuting Attorneys Association proposed a change to Rule 3.8 of the Ohio Rules of Professional Conduct – which lays out the special responsibilities of prosecutors – and announced best practices for conviction review by prosecutors.

The proposed rule change “would make clear an ethical obligation that prosecutors already recognize and practices that they already undertake regarding new, credible, and material evidence of a convicted defendant’s innocence,” the association stated. Noting “[a] prosecutor’s responsibility for pursuing justice extends beyond the date of conviction,” the association advocates for the creation of independent conviction review units, when feasible, in Ohio prosecutor offices.

Cummings supports reinforcing the understanding that a prosecutor’s obligations are to justice – not only before and during a trial, but also after a conviction. She maintained that this ethical emphasis is vital, but is only “one tool in the toolkit” needed to fix the problem of wrongful convictions.

Judge Zmuda told Court News Ohio that recognizing and appreciating the contributions of prosecutors is critical to advancing the criminal justice system. He sees prosecutors who have a more expansive view of their work – as in Philadelphia – and those who have spent their careers over decades “putting many bad guys away.” He hopes this moment for change isn’t missed.

“This effort should not be seen as an attack on prosecutors, but as an opportunity – given advancements in science and the like – to improve the justice system,” he said. “When we see opportunities to improve, we should seize them, vet them, and implement them, where appropriate.”

Also essential in the toolkit for remedying wrongful convictions, according to Cummings:

- Updating criminal procedure and evidence rules

- Ongoing education and training for prosecutors, particularly on the prosecutor’s requirement to turn over any evidence favorable to the defense

- Ensuring a postconviction right to counsel

- Addressing postconviction statutes

- Correcting convictions that relied on “junk” science.

Judge Zmuda said the Ohio task force is studying all the “tools” Cummings identified. While Cummings and Krasner are clearly fans of local conviction integrity units in prosecutor’s offices, the Ohio task force is exploring the pros and cons of the different models. It’s also reviewing criminal and evidence rules and the postconviction process in Ohio for useful changes, Judge Zmuda explained.

“We’re seeking a process that is effective in achieving justice,” said he said. “Justice doesn’t end with a conviction or acquittal. It ends when we got it right.”

CREDITS: