The Whole Truth

There are lots of misconceptions about jury duty. Here are 11 facts from court jury managers and former jurors about how juries really work.

Credit: Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Deep in the day’s mail is a surprise – a jury summons. The first response for many might be dread. The inconveniences immediately pop to mind: missing work, changing schedules, commuting to an unfamiliar courthouse. But people often carry misunderstandings about how juries operate and what’s involved in jury duty. Jury commissioners say that if people can overcome their mistaken beliefs, they will become quite invested in doing the job fairly and ultimately feel that they made a valuable contribution.

The Truth: Not all juries have 12 people

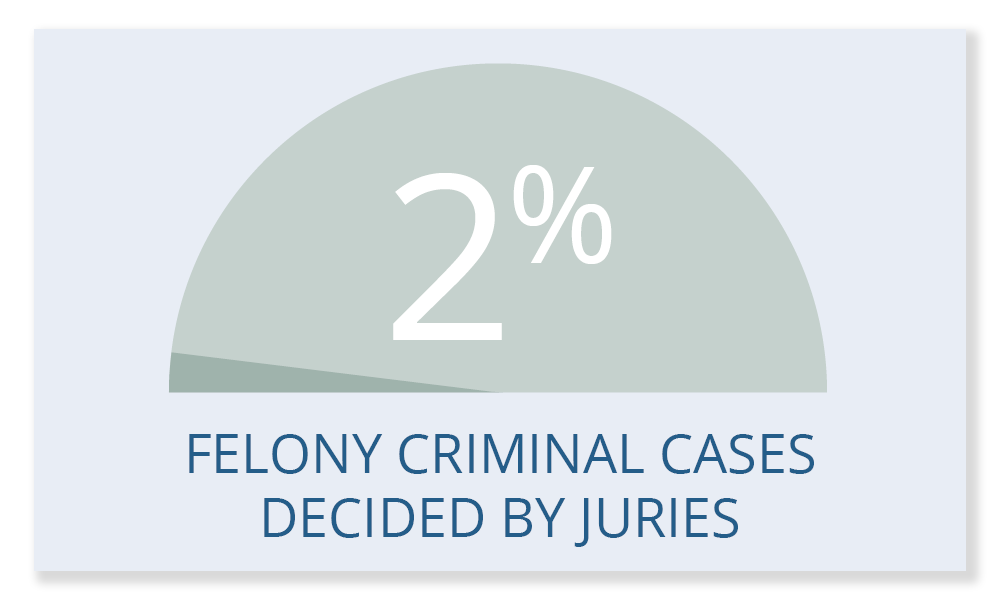

A jury of 12 is what most people are familiar with from television shows or the news. Those are typically high-profile trials – such as the recent murder trial of William Husel about fentanyl administration in a Columbus hospital. The number of jurors, though, depends on the type of case – and whether it will be heard in federal or state courts, and in which state.

Bob Condon, the jury commissioner for Franklin County Municipal Court, frequently has to dispel this confusion.

“People who receive a jury summons will call worried that they’ll be seated on a murder trial,” Condon says.

But, he explains, municipal court is different from what people expect, even for criminal charges. Ohio’s municipal, and county, courts hold trials for allegations of misdemeanor crimes – such as disorderly conduct, vandalism, or possession of certain drugs. When these cases go to trial, only eight jurors are required.

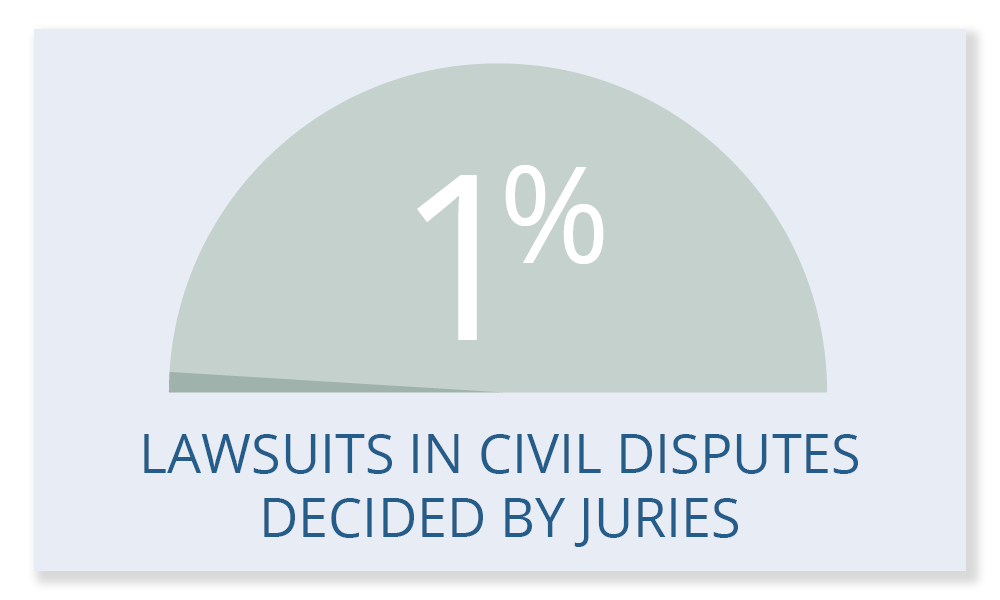

Then there are civil cases, which usually involve disputes about or claims for money, as in foreclosures, personal injury claims, or contract disagreements. Civil lawsuits – heard in common pleas, municipal, or county courts – seat varied numbers of jurors, with many juries composed of six or eight members. Condon says if you’re seated on a civil case in Franklin County Municipal Court, there will be six jurors, plus alternates.

Charges that someone committed a felony, though, require the better-known 12-juror setup. Trials for these more serious crimes – such as drug trafficking, motor vehicle theft, rape, and murder – are conducted in Ohio’s common pleas courts.

The Truth: Serving on a jury may take only a few days

How long you will be needed as a juror hinges on the type of case. Condon notes that people summoned for jury duty think all trials take a couple weeks. They also expect to be sequestered, in a hotel, away from family and home. For municipal court cases, he explains, trials more typically last two to four days. And, although it’s not guaranteed, you will likely go home each night, he says.

Even trials for murder or other felonies can be shorter than a week or two. Janna Conley of Columbus served on a jury last August involving a shooting. The defendant was charged with attempted murder, felonious assault, and other crimes. She says the trial in Franklin County Common Pleas Court lasted three days.

Yet there are complex cases – such as the Husel trial, which had allegations involving 14 patients – that may require weeks for juries to hear evidence and to deliberate.

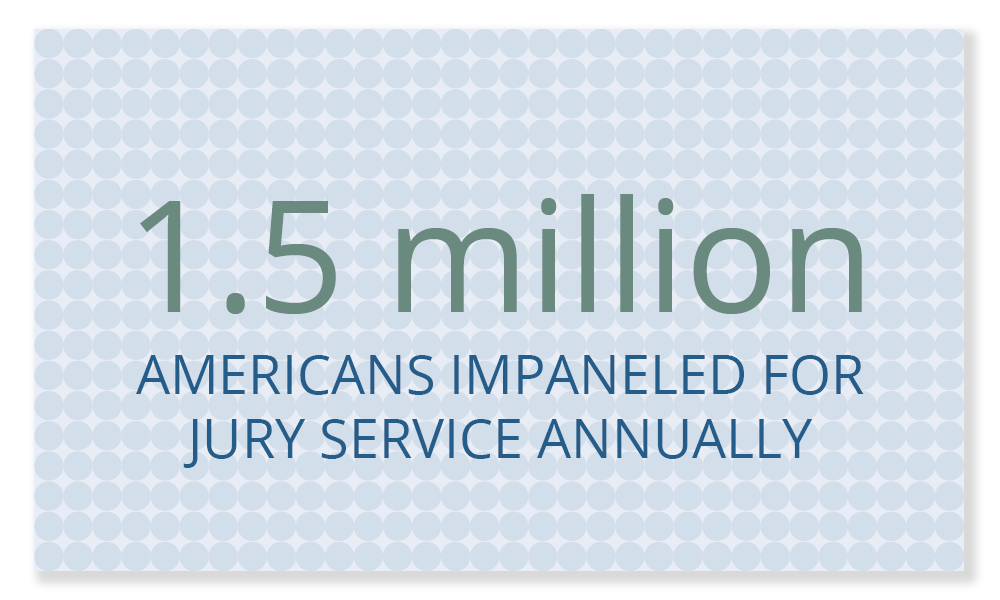

The Truth: Not everyone who is called for jury service will be placed on a jury

Condon says he summons 22 to 25 possible jurors for each municipal court case, to seat the jurors and alternates the court needs for a trial. Brad Seitz, jury commissioner for the Hamilton County courts, summons 650 people every week to cover both common pleas and municipal court trials. He’ll call in about 30 in person for each criminal case and 20-24 for other trials. Jury managers ideally identify enough qualified people so a jury can be selected from that group without pulling in more prospective jurors.

For criminal and civil trials, lawyers from each side will question potential jurors. The judge may ask questions as well. The purpose is to ascertain whether a prospective juror can be impartial. One problem, for example, may be if a potential juror knows someone in the case.

Conley, the Franklin County juror, notes that the process, called voir dire, was surprising to her.

“I thought each individual would be asked the same questions,” she says. “And the questions weren’t what I expected.”

One she recalled was, “If only one person testifies about what happened, how much would you believe them?” Others in her jury pool were presented with a scenario: If three people said they saw a couple kissing at a wedding but disagreed how many times they kissed, how certain would you be that the pair kissed at least once? What if there were six people who said they saw the couple kiss?

She says the questions made sense later, because the murder accusation depended heavily on the testimony of one eyewitness.

If you’re a prospective juror who is excused during this questioning, it doesn’t mean you did anything wrong, jury managers note. Each side can ask to excuse a juror without giving a reason – which is called a peremptory challenge. Potential jurors also can be dismissed for a good reason, known as “for cause.”

The Truth: Jurors might be able to ask questions or take notes

It was unexpected when Seitz mentions that a few judges in Hamilton County courtrooms allow note-taking during trials. But Ohio’s rules for criminal and civil jury trials permit jurors to take notes and also to ask questions of witnesses. There is one overriding, and crucial, caveat, however: The decision is left to the judge. In practice, the ability to do either is not universal, or even common, because each judge either approves of jury note-taking or does not.

Seitz explains that if you’re on a jury allowed to take notes, you’ll use court-provided paper and pens. You can use your notes during deliberations but can’t take them home. After the verdict, your notes are destroyed.

If a judge allows jurors to ask questions during a trial, there are several requirements. Among them, you as a juror must submit the question in writing to the court, the judge will give the attorneys the opportunity (away from the jury) to object to the question, and the judge ultimately decides whether the question will be asked.

What’s more common to hear about in Ohio are juries that ask questions during deliberations. These inquiries are made in writing. Seitz notes that each deliberation room in Hamilton County has a phone. The jury foreperson can call the bailiff, who then stops by to pick up the written question and deliver it to the judge.

The Truth: Juries sometimes make decisions other than determining guilt

If you’ve mostly heard about criminal cases, it’s important to be aware that jurors in civil cases don’t weigh whether someone is guilty of a crime. They instead decide how to resolve the dispute and whether and how much to compensate the parties involved in the lawsuit.

There also is a special type of jury, called a grand jury, that doesn’t decide guilt – and that does its work before a person can be charged with a crime and put on trial. Grand juries have a completely different mission. More on that soon.

In criminal trials, though, the jury does decide whether a crime has been committed and whether the defendant is guilty – specifically, whether the evidence proved beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant committed a crime.

In the deliberations that Conley was part of, there were differing opinions about the allegations. The jurors quickly coalesced toward one point of view, though, based on the evidence, or lack of it, she says.

“Someone was shot a bunch of times, so no one disagreed that something bad had happened,” Conley says. “But the one eyewitness was unbelievably unreliable.”

“We wanted to talk through it, though, to feel comfortable with our decision,” she explains. The jury agreed that the defendant was not proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

Grand juries have a purpose distinct from jurors who are seated for a trial. The unique obligation is explained in this video.

The Truth: Jury decisions don't always have to be unanimous

For the trial Conley served on, the verdict was required to be unanimous. Ohio calls for jury unanimity to convict someone of a crime. In fact, the U.S. Supreme Court reiterated this view for the entire country in a 2020 ruling. The right in the U.S. Constitution to a trial by an impartial jury means a jury must reach a unanimous verdict to convict a person of a crime, the Supreme Court concluded. The decision overruled a 1972 decision that had upheld practices allowing non-unanimous criminal verdicts in two states.

Other types of juries, however, don’t need a unanimous vote, the jury managers note. In civil cases, a vote of three-fourths of jurors decides the verdict.

The Truth: A special jury meets before a person is charged with a crime

When prosecutors are seeking to indict a person for a felony crime, they must present their arguments to a grand jury. Instead of determining guilt, grand jurors assess whether the state showed enough evidence to make the accused face charges of a crime.

“I didn’t know before I was on a grand jury that we were just deciding probable cause – whether there was enough evidence to indict,” notes a 47-year-old corporate communications manager who was called for grand jury duty last year in Delaware County.

Grand juries are made up of nine jurors. Seven must vote to indict, then criminal charges can be filed. Grand juries are described in a state Supreme Court video as “a sword” that authorizes the government to prosecute, as well as “a shield” to protect a person from being charged with a crime by the state without sufficient evidence.

If you’re selected as a grand juror, the schedule will be more unusual than for trial jurors. In Delaware County, grand jurors report one day a week for about two months, the communications manager notes. In Cuyahoga County, service on a grand jury is two days a week for four months if selected. Montgomery County grand juries also work for four months. The commitment for Hamilton County grand jurors, Seitz explains, is every weekday for two weeks.

The communications manager, who is a mother of three, points out that her summons in the mail clearly explained the schedule. When she was seated, it was the first time the 22-year county resident had served on any jury. Each day was busy. She says the grand jurors didn’t know how many cases they would review each day, but it ended up being roughly 15 cases.

Grand jurors can ask appropriate questions. The communications manager explains that the county prosecutor first made the state’s case for an indictment, presenting witnesses in support. Then grand jurors followed up with questions. She says they, for example, asked law enforcement questions about timelines or where things were found.

The Truth: Jurors may wish they knew more

Conley says she and the other jurors really wanted to know what had happened in the case they heard.

“I wanted to see the TV movie, where all the details are explained and we would see how it turns out,” she remarks. “There’s always the comparison to ‘Law and Order.’ How different it was for us to decide our case with what we had.”

The Delaware County grand juror notes her group also couldn't help but be curious.

“We got invested and intrigued,” she says. “Sometimes the grand jury wanted to solve the crime.”

The Truth: Jurors can't research the case, defendant, witnesses, or terms used

As a juror, you may naturally want to gather more information about the case being heard. However, these attempts to learn more are absolutely prohibited. You must decide the case based on the facts and evidence presented in the courtroom. To ensure a fair trial, it's essential to not be influenced by outside information, which may be unreliable or irrelevant and can't be challenged in court by each side in the case.

With the growing use of smartphones, the issue has become even more troublesome because it’s so easy to look up anything. But research, even Googling a term like “accomplice,” is juror misconduct, explains Reeve Kelsey, a retired Wood County Common Pleas Court judge.

In a video on the topic, Kelsey, who served on the court for 20 years, highlights another instance of inappropriate research from a famous Warren County case. In 2009, Ryan Widmer of Hamilton Township was on trial, accused of drowning his wife, Sarah, in their home. He had called 911, saying he found his wife submerged in the bathtub. On the 911 recording, the operator instructed Widmer to remove his wife from the tub and perform CPR. The jury also could hear emergency responders arriving.

At trial, an EMT testified that Sarah’s body was dry when they got to the scene – which established the time between Widmer removing his wife’s body from the tub and the emergency responders’ arrival. Kelsey says several jurors went home that night, took a shower or bath, and calculated how long it took them to air dry. They shared their findings with other jurors. The result: a mistrial.

The Truth: People are confused about whether they can serve, and what's involved

Seitz notes that potential jurors with a felony conviction are often baffled about whether they can sit on a jury. If you’re still serving sanctions related to a conviction, you cannot serve on a jury, Seitz explains. But once the sanctions are completed, you cannot be excused from jury duty for having a conviction.

Seitz also points out that some employers that can’t pay their employees for jury service hesitate to write a letter stating that fact, thinking the organization will get in trouble. However, this employer financial limitation allows a juror to be excused, he notes.

Condon says he receives many calls from people wanting to avoid jury duty.

“Some people just ask to be excused before they even know what it is they need to do,” he notes.

Jury managers rely on state law, which spells out when potential jurors can be excused and when deferrals are allowed. Just the idea of jury service seems to be the hardest part for the public, so jury managers take time to talk with people who are summoned.

“You learn to hear nervous tension,” Seitz says. “I reassure them that we will walk them through every step of the process.”

“Sometimes a phone call may last 20 minutes,” Condon adds. “I find myself talking people into serving at least once a day.”

It comes down to treating people with respect and kindness, they say.

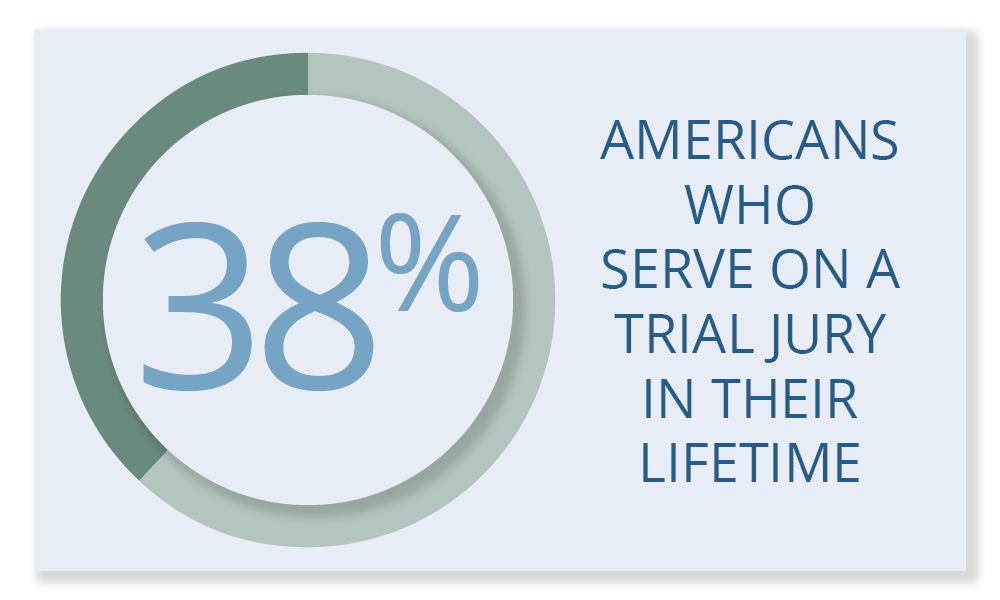

The Truth: It matters that people serve on juries when called

With every case, Condon and Seitz watch the initial reluctance of selected jurors dissipate as they sit in the courtroom and consider their cases.

“They learn how the system works,” Condon explains. “I see jurors bend over backwards to be fair. Afterward, they are excited to tell you what happened. … Most will tell you it was the best experience of their lives.”

The jurors who shared their experiences both mention how organized the entire process was. In Delaware County, the grand jurors received a half day of training on the types of drug offenses, various felony classifications, and overall grand jury responsibilities. Conley says the Franklin County judge “did an excellent job” explaining terms, such as stipulations, and what they meant for the jury. The jurors both clearly took pride in the responsibilities.

“I wanted to do the right thing,” says Conley. “I wanted to perform my civic duty – do my part, do it well, and take everything into consideration.”

“It was an honor to be selected,” the grand juror adds. “These are our neighbors. We live among them. We wanted to make sure we were giving it our best.”

Jury commissioner Condon, who sometimes asks potential jurors to consider how they would feel if they were on the other side of the law, stresses the importance of seeing one’s peers in the jury box. That’s at the heart of the legal system – to ensure fairness, and achieve justice, for everyone in the community.

“The biggest misconception is the importance of just being there,” Condon says. “For the jury system to work, we need everyone’s involvement.”

Additional Sources: National Center for State Courts: Center for Jury Studies, National Constitution Center, Ohio Jury Management Association, and Ohio State Bar Association “ Law Facts: Jury Service” pamphlet.

CREDITS:

Design: Ely Margolis

Web: Erika Lemke