On Behalf of Children

Courts rely on guardians ad litem to discover how cases, from truancy concerns to abuse allegations, impact a child’s life. Insights from GALs help judges and magistrates understand what’s best for a child.

The family landed in court because one parent was charged with domestic violence against the other. Given the situation, the care of the couple’s 10-year-old child also was a concern, for the short and long term. So the judge appointed a guardian ad litem – Jennifer Himmelein.

Himmelein’s mission was to gather details about the child’s life and recommend to the court what would be best for him. That’s rarely a simple determination. Himmelein first learned the boy wasn’t attending school. While spending time with him, she noticed a tic and an unusual way of speaking, plus a lack of eye contact. She asked the parents about the issues, but they were unwilling to acknowledge any concerns or take the child for testing.

As the guardian ad litem, or GAL, Himmelein was able to request an order from the court for an evaluation. That assessment gave the court a more complete picture to make a better decision about the child’s care while the parent’s case moved through the legal system.

On the child’s behalf, Himmelein also visited his home to learn about the family circumstances, and she talked to school officials. Ultimately, the mother received custody of the child and agreed to keep him enrolled in school. Based on his diagnosis, the boy received services and Social Security benefits.

“If I hadn’t been appointed on the parent’s case, the child’s issues wouldn’t have been addressed,” notes Himmelein.

Guardians ad Litem Appointed for Particular Cases

Guardians ad litem are different from guardians. In Ohio, probate courts name guardians to handle the personal or financial matters of an adult or a minor due to a legal or mental incapacity. Guardians ad litem, though, aren’t about incapacity. Courts appoint GALs for children in specific cases to identify the child’s best interests and to relay that to the court.

In Ohio, a GAL must be appointed when there is a claim of abuse, neglect, or a lack of adequate parental care for certain reasons (called “dependency”). Courts also are mandated to name a GAL if a child who is allegedly delinquent or unruly has no parents or the child’s interests don’t align with the parents. In the rest of delinquency or unruly cases, the court has discretion whether to appoint a GAL. GALs also can be called on when a court is determining legal custody, parenting time, companionship, or visitation.

GALs are instrumental in giving courts a firsthand look into a child’s health and well-being, and the child’s world – at home, at school, and elsewhere.

As Himmelein did, GALs are required by Ohio court rules to interview the child, as appropriate for age and developmental stage, and they must visit the child where they are living or might be living in the future. They also talk with others in the child’s life, such as foster parents and relatives, who could have relevant knowledge. GALs connect with school personnel, medical and mental health providers, child protective services workers, and court staff to build an informed view of the child.

Himmelein, an attorney who served as a GAL for about 12 years, notes that the cases GALs work on often involve parents with mental health or substance use disorders. Sometimes the kids are struggling with these issues, too.

Guardians ad Litem Assist Courts by Learning About Children

Whatever the type of case, whether in juvenile, domestic relations, or family court, a GAL’s insights help judges and magistrates.

“It allows courts to better understand the case,” says Magistrate Michelle Edgar of the Fairfield County Juvenile and Probate Court, led by Judge Terre Vandervoort.

That’s because a judge or magistrate can learn only limited information during courtroom hearings. Yet to make good decisions for a child, the court needs to know now what’s happening in the child’s life outside of court, Edgar explains. GALs do a lot of work with the children before appearing in court – often visiting the child’s home or school and talking to providers before the first hearing.

Himmelein, now a magistrate for Judge Colleen Falkowski in the Lake County Domestic Relations Court, adds, “If there are serious parenting concerns, I want a GAL on a case as soon as possible.”

Himmelein describes a case where a single mom left her kids at home one night and went out with her boyfriend. The mother ended up in a situation where she got arrested. While the mother was going through the legal system to resolve her charges, her children had to be cared for and protected. There was no time to wait for a trial or a case to wrap up, Himmelein says.

Enter the GAL – who went into action, interviewing the kids and others and making a recommendation to the court for the immediate future, and eventually for the longer term.

Each Case and Child Is Different

There is no one-size-fits-all answer in cases in which GALs are appointed. What will be in a child’s best interest depends on each child’s distinct circumstances.

Erinn McKee Hannigan takes appointments as a GAL in Hamilton County Domestic Relations Court. The attorney and mediator is called in private custody cases when a parent wants a judge to speak privately to a child or when a court approves a parent’s request for a GAL. McKee Hannigan tailors her recommended solutions to the child.

“As a GAL, it’s important to listen closely. There are nuances you pick up on,” she says.

She was a GAL for a 16-year-old whose mother filed to terminate joint custody with the father because of something said in a disagreement. The teen told McKee Hannigan that she enjoyed spending time with her dad and wanted him involved in decisions for her life, such as her extracurricular activities and where to apply for college. But she loved her parents and didn’t know how to tell her mom that she didn’t want a change to the custody arrangement. McKee Hannigan was able to articulate the teen’s wishes to the court, which decided to keep both parents involved.

In another case, the parents were so wrapped up in their conflict that they didn’t see the impact on their daughter, who wouldn’t go to school, McKee Hannigan says. As the GAL, McKee Hannigan was unable to work with the parents and instead explored options through the schools. She helped to find an alternative educational program with a specialized approach, and the court ordered the teen’s participation in the program. A few years later, McKee Hannigan received a text message from teen saying she had received her high school diploma.

“GALs can make an impact in ways that others wouldn’t comprehend,” McKee Hannigan says.

In Fairfield County, Edgar handles a lot of truancy cases that necessitate digging deeper for answers. She finds that beneath a child’s ongoing absences from school often lies health issues.

One child who was missing school complained of ongoing dizziness. Edgar needed the GAL to help the family identify the source of the dizziness. Was it medical? Was it caused by something else? The GAL was integral in finding the right medical care for the child. It turned out that the child had a learning disability. The GAL’s efforts to make sure the child attended the testing and other appointments revealed a need for a different learning environment due to the disability, Edgar notes.

“This may not have been identified, or might have been identified much later, if the GAL had not been so involved with the family and the case,” she says.

Edgar, who was a GAL in cases for 10 years before becoming a magistrate, is unexpectedly seeing a trend of “timid young women” in her courtroom for truancy. It’s a growing issue since the COVID-19 pandemic began, she notes. In one study conducted in the United States, nearly half of the female high school and college students experienced a significant increase in anxiety during COVID-19. Edgar says many girls in court have a debilitating level of anxiety preventing them from making it to school.

“These cases become more problem-solving than adjudicating,” Edgar notes. “We’ll work on persuading the child to get to school for one class. Or one day. Sometimes the win is the child going to school a couple times a week.”

Holly Davies, a Stark County attorney who has been serving as a GAL for 20 years, notices that good recommendations depend on thoughtful consideration about often complex circumstances.

She was the GAL for a girl who spent years with a foster family after attempts to place the child back in her original home failed. Over time it was unlikely that the girl would return home permanently, and she had bonded with the foster care parents. Then one of her relatives surfaced and wanted to care for her.

Davies had to evaluate many issues. There were religious, cultural, and racial differences to weigh, she says.

“I had to consider, ‘What is best for this child?,’ not what was easiest,” she notes.

Davies recommended the child’s adoption by the foster family – which recently was finalized.

“I fought for that child to be with those who the child knew as family,” she says.

Court Appointed Special Advocates Help, Too

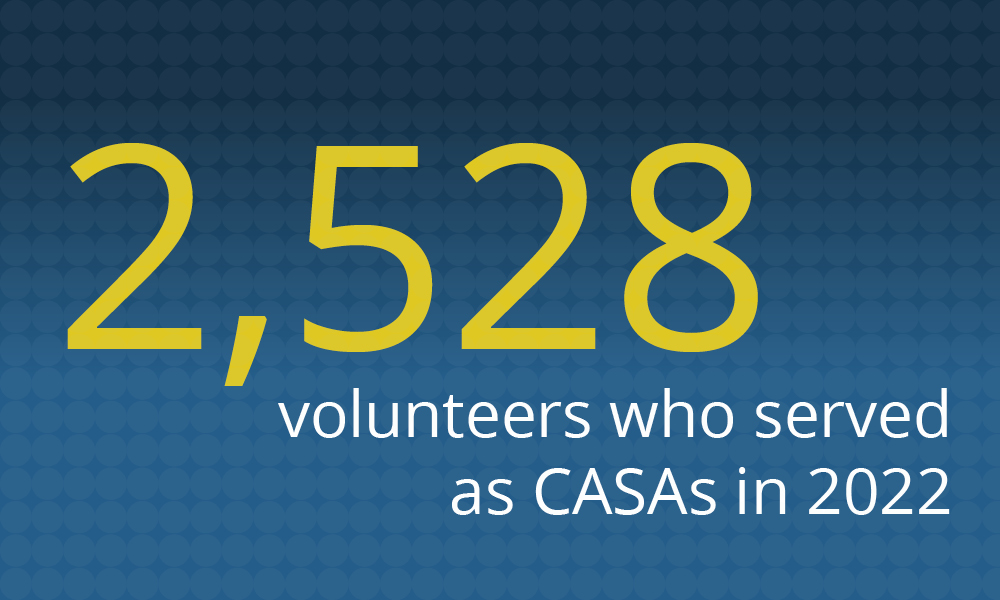

The volume of cases where courts need to learn a child’s circumstances and best interest is substantial. With abuse, neglect, or dependency allegations, for example, courts are required to appoint a GAL. In 2022, there were 18,568 of these cases in Ohio. To assist with the demand, courts sometimes choose a specially trained volunteer, called a court-appointed special advocate (CASA), as the GAL. CASAs also are tasked with identifying a child’s best interests for the court.

In courts that direct that GALs must be attorneys, a CASA can still be named to assist as a “friend of the court.” Volunteers from Ohio CASA, which has programs in 58 counties, served 9,962 children last year.

Specialized education is required to act as a GAL or CASA. CASA volunteers must be 21 or older, pass a comprehensive background check, and complete 30 hours of education from a national organization before taking an assignment from a court. CASAs must then take 12 hours of continuing education each year.

For GALs, 12 hours of coursework from designated providers, including the Supreme Court of Ohio, must be completed before accepting a court appointment. After that, GALs need six hours a year in continuing education.

The time commitment for GALs varies by type of case. Abuse, neglect, and dependency cases can take up to two years. To serve as a GAL, attorneys can contact the local court and fill out its application for placement on the court’s list for appointments. The GAL pre-service education must be completed, and applicants should check the court’s local rules for other requirements.

Educating Parents on GAL Role Essential

GALs learn many skills for navigating cases, but they aren’t always popular in their determinations.

When Himmelein was a GAL, she talked with parents as soon as appointed. She would explain her role – to delve into the child’s life and develop suggestions that will be in the best interest of the child.

She told parents, “At the end of this, I can guarantee that you won’t like me, because I will inevitably make some sort of recommendation that you don’t like or agree with.”

She empathized with them, understanding that no one wants their parenting judged by someone else.

“You don’t want to step on parents’ toes,” Himmelein says.

“Remember the focus is the kid,” adds McKee Hannigan, who started doing GAL work in 2002. “Our job is to look at a situation through a lens where we see kids first.”

She urges GALs to be open and honest with parents from the beginning. She sets boundaries with them, particularly stressing that she isn’t their attorney.

Edgar says that ongoing dialogue with the parents helps to build rapport and trust. A GAL shouldn’t surprise parents with what is recommended and needs to give parents time to learn a different way to do things, she notes.

“The goal is to help the whole family to heal – to function and thrive outside of court,” she says.

For Davies, it’s also essential to be respectful of the parents regardless of whether you agree with what they’re saying or doing.

“They love their children. Most parents think they’re doing what’s best for their kids,” she explains.

She encourages GALs to educate themselves on cultural and socioeconomic differences. And to ask the court to let them step back if the case isn’t for them.

“If you’re not feeling open-minded, if you have a problem with a particular religious view or political view, then don’t be the GAL on that case,” Davies recommends.

Advice for Courts, Strategies for GALs

To keep good GALs, courts need to support them, these magistrates and GALs stress. Allot enough time for GALs to investigate a child’s circumstances, reign in parents who have unrealistic expectations, and put orders in place as needed so GALs are paid, Himmelein suggests.

When courts work to recruit and retain good GALs, and GALs stay on top of their skills, children and families ultimately benefit. The Ohio Judicial College offers many classes to assist. The initial education required before serving as a GAL is the focus of a class on May 3 (“Pre-Service Course”). Among its other ongoing courses for GALs, the College will hold an afternoon of instruction on April 11 about understanding the role of child protective services in court cases.

Davies points out that people taking on this type of work also need to be sure to take care of themselves.

“Every day GALs are just absorbing others’ trauma, and toxic photos and stories,” she says. “A lot of the work is done in the evenings or on weekend mornings. It can be hard to turn off.”

Courses through the Judicial College explore how to deal with secondary trauma.

McKee Hannigan turns to running for stress relief. She did a Florida 10K and a half marathon back to back in February. On tough days, she reflects on the children she was able to help. And she’ll call her own kids to lift her spirits.

Davies talks with her law partner to process the experiences, and she meets periodically with a group of women lawyers for strength. She also has been rewarded by touting the value of school to the children and teens she assists.

“I tell the kids that education is your escape if you don’t want to continue living in this life,” she says.

It was a conversation she once had with a pregnant teenager. Davies was the teen’s attorney, and Davies’ law partner became the GAL. Years later, the law firm was hiring a staff opening, and they received a letter from an applicant who said they might remember her. After going through court, the young mother had followed the recommendations for her safety and protection, participated in counseling, learned tools for successful parenting, and found stable housing.

“She put herself through college, then went to law school,” Davies adds.

Davies and her law partner hired the woman.

“She is our pride and joy. Our success,” Davies says.

It’s the kind of meaningful moment that inspires GALs to stay the course and help the next child.

CREDITS: