New Options for Domestic Violence Victims

Among the latest advances are laws that take domestic violence more seriously and give victims a greater voice. And services include a self-help website for seeking protection through courts and finding in-person legal guidance.

Paula Walters credits “a nosy neighbor” with saving her life. Walters, a paramedic, was living with her boyfriend in a house in Henry County. The neighbor knocked on the door one day while Walters was being strangled by her boyfriend. The knock stopped the attack.

Walters was taken to the hospital on that day in 2006, and she filed a police report. She said her boyfriend hit and kicked her and he strangled her causing her to pass out. Staff at the hospital knew her boyfriend, who worked in law enforcement. A doctor asked her, “What did you do to make him so mad?”

Walters, who shared her experiences in October at an Ohio Domestic Violence Network event, said her boyfriend was charged with felonious assault, pled to a misdemeanor, and was placed on probation and fined. Walters was treated at the hospital for extensive visible bruising, including around her eyes, mouth, and face. But those were only the injuries the medical staff could see. Over the ensuing years, her symptoms, such as dizziness, worsened. Doctors diagnosed her with a dozen ailments and prescribed 22 medications. In 2019, 13 years after the attack, doctors finally landed on a clear diagnosis – traumatic brain injury. It was caused by the oxygen deprivation to her tissues and organs that occurred during the strangulation. Walters began a slow process of recovery from her injuries.

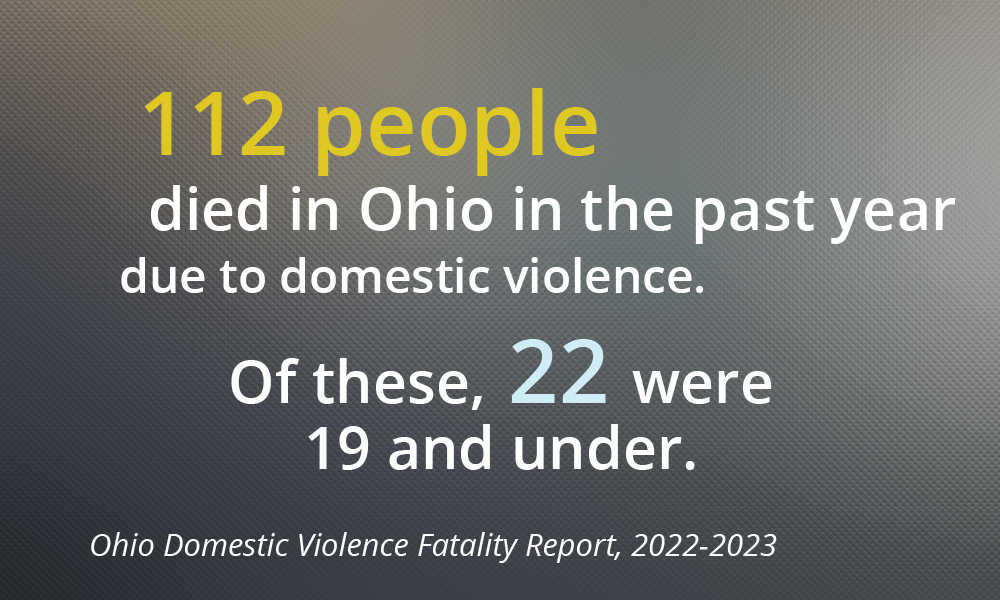

Accounts from victims like Walters are disturbing, but sadly not uncommon. The National Coalition Against Domestic Violence reports that 10 million people are physically abused each year by an intimate partner and 20,000 calls are made every day to domestic violence hotlines.

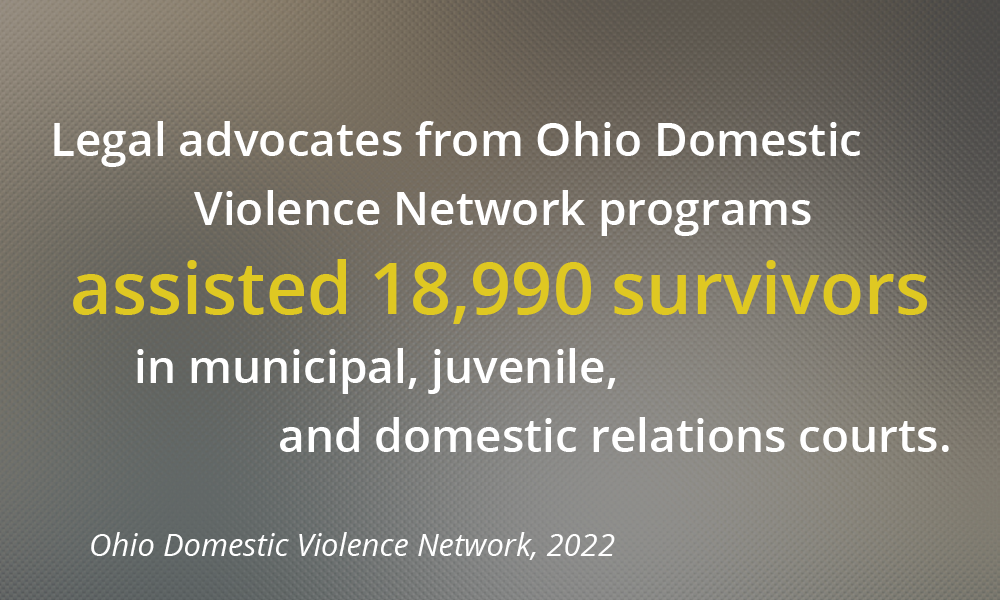

Ohio courts and the legal community have assisted and protected victims of domestic violence and held offenders accountable with the tools available. Those measures are evolving. New laws are being applied in the courts. Resources to get victims the help they need are expanding. And courts continue their programs for offenders to change dangerous behaviors.

Strangulation Now a Felony

Among the new laws, Ohio this year made strangulation – obstructing someone’s normal breathing or blood flow – a felony offense even when it isn’t fatal. Taking nonfatal strangulation seriously is crucial because it is frequently a precursor to murder in domestic violence cases, said Ruth Downing, a forensic nurse, at a recent webinar coordinated by the Supreme Court of Ohio Domestic Violence Program on the new law. Research shows that women who have been strangled and lived are seven times more likely to later become a victim of homicide.

Before the new law took effect in April, prosecutors could charge a nonfatal strangulation case as felonious assault, explained Alexandria Ruden, a supervising attorney for Legal Aid Society of Cleveland. Ruden coauthored “Ohio Domestic Violence Law” with retired Cleveland Municipal Judge Ronald Adrine and Cuyahoga County Common Pleas Judge Sherrie Miday. The threshold for a felonious assault conviction is high because it requires proving serious physical harm or temporary substantial incapacity. Ruden said advocates reported that strangulation was charged as felonious assault only if there were significant external injuries or a clear loss of consciousness.

“The challenge with nonfatal strangulation is it is very dangerous but results in visible injuries only about 50% of the time. In fact, pathologists have said victims can die from strangulation without any exterior marks,” Ruden said.

Brain injury or memory loss are two injuries without external marks that can result from the restricted or blocked blood flow to the brain during strangulation. Someone who has been strangled can die from internal injuries as much as 36 hours later, Downing said. She added that victims who are strangled often don’t realize it when they lose consciousness – which can happen within six seconds. Death can occur in as little as two minutes.

“Without the understanding of the medical piece, some cases got treated much less seriously than they should,” Ruden said. They were often prosecuted as misdemeanor offenses.

Courts Sort Out New Felony Criteria

Judge Marianne Hemmeter of the Delaware Municipal Court explained that the new strangulation law gives courts specific guidance. There is now a definition for strangulation, and the law also defines suffocation. The level of the felony depends on whether the accused created a risk of physical harm or caused harm, and the seriousness of that harm. Based on these factors, the accused could be convicted of a fourth-, third-, or second-degree felony.

Judge Hemmeter, who deals with domestic violence cases every day, raised a key consideration at the webinar on the new law: “What does ‘serious physical harm’ look like when an injury isn’t visible?”

“This is where the use of experts becomes very important,” she said.

A greater understanding of the physical symptoms of strangulation will enable law enforcement, prosecutors, defense counsel, and courts to effectively handle these cases. Lesser known physical symptoms that point to strangulation include red spots in the eyes, vocal changes, headaches, and vomiting. Loss of consciousness also indicates strangulation. Given that victims often don’t realize they lost consciousness, medical professionals, law enforcement, and those in the justice system need to know what symptoms indicate that a victim passed out, said Ruden. She stressed the importance of law enforcement and health professionals documenting the signs and symptoms for prosecutors and for presentation to the court.

Judge Hemmeter said that collecting as much evidence as possible, similar to how murder cases are investigated, will be essential. She noted that, due to the nature of strangulation cases, it is important to bring expert testimony about the injuries to trial. Courts have approved police officers and emergency room nurses as expert witnesses if they are trained in the signs and symptoms of strangulation, she said.

Charges alleging strangulation under the new law are already climbing in parts of the state. In Stark County, they have added a fourth day for grand juries because of the volume, said assistant prosecutor Jennifer Dave.

Judge Hemmeter noted that the impact of the new law will likely reach beyond criminal cases.

“I expect that allegations of nonfatal strangulation will also become issues for domestic relations courts deciding custody and visitation issues,” she said.

Marsy’s Law, Victim Rights, and Court Obligations

This year, new laws were put in place to implement the requirements of Marsy’s Law, a constitutional amendment approved by voters to protect victim rights. The expanded rights guaranteed by Marsy’s Law apply to victims of domestic violence as they do to any crime victim. Marsy’s Law details an array of rights, such as updating victims on the status of the court case, protecting them from the accused, shielding the victim’s identifying information from disclosure to the public, notifying victims about public court proceedings, and that they can attend and be heard at the proceedings. Courts also have a bigger role to play because they must be certain a victim’s rights are upheld throughout the legal process. That court responsibility carries through to the end of the case or to the offender’s completion of the sentence.

Judge Hemmeter noted that before Marsy’s Law and the new statutes, a domestic violence offender could enter a plea without any victim input.

“Now it’s a much more transparent process. Courts are checking at many points that the required steps are taken. We want to make sure everyone is on equal footing,” she said.

In light of the changes, Judge Hemmeter found she had to shift her approach in a domestic violence case last month. A woman alleged that her husband assaulted her, but then recanted her allegation. To comply with Marsy’s Law, Judge Hemmeter will need to be sure that the woman is kept informed about the case even though she recanted.

“She now has constitutional rights,” the judge noted.

The woman will be told she can take part in the legal proceedings. She can appear in court and make her wishes known, whatever those wishes are.

“Marsy’s Law has made courts look at our role in ensuring that victims understand the legal process and that their voices are heard,” Judge Hemmeter said.

The judge said she also speaks directly to victims much more since Marsy’s Law was approved. Before, the prosecutors or victim advocates in the municipal court would take the lead on guiding victims through the prosecution of the case. But now, as the judge, she is obligated by Marsy’s Law to explain the legal process to victims of crime.

The Summit County Domestic Violence Intervention Court (DVIC) has victim notification already built into its process. The DVIC, which launched in 2011, was certified as a specialized docket by the Supreme Court in 2019 to offer treatment, counseling, education, and an alternative to prison to certain domestic violence offenders with diagnosed substance abuse or mental health issues. Program coordinator Christina Claar said the victim advocates take part in the regular meetings the offenders must attend. The advocates then update victims about what’s happening with the offender and the case, Claar said.

Kelli Anderson, who supervises the DVIC and the domestic violence unit in the Summit County Adult Probation Department, said the officers in her unit make multiple attempts to notify victims and document the efforts. The notifications about the proceedings and their rights becomes more difficult if victims move but don’t update their contact information with the court.

To assist courts with understanding the obligations to crime victims, the staff of the Supreme Court Office of Court Services can help identify considerations and duties for courts when notifying victims and for handling continuances, pleas, discovery, testimony, restitution, and more. More targeted guidance is also available for juvenile courts and for clerks of court.

Privacy Versus Referrals

The law’s enhanced protection of a victim’s personal information has led to an unanticipated wrinkle for advocates who combat domestic violence. Lisa DeGeeter of the Ohio Domestic Violence Network explained that law enforcement in the past would share reports of domestic violence with advocacy groups so they could offer victims assistance, safety planning, and referrals to local programs and community services.

“That has come to a standstill in many communities,” DeGeeter said, explaining that law enforcement is concerned about disclosing victim information, given Marsy’s Law. “Victims are now not getting referred to the help they need.”

A July fix to the legislation said that law enforcement can share the reports with “designated agencies.” But DeGeeter noted that the phrase wasn’t defined. Advocacy groups plan to work with the state prosecutors’ association to find a resolution.

Website Assists With Obtaining Protection Orders

In the last few years, more resources can be found online to help victims of domestic violence – and those include places to find step-by-step guidance for getting a protection order.

If someone is being threatened or harmed, certain courts can issue a protection order. There are protection orders not only for domestic violence but also to address dating violence, stalking, or a sexually oriented offense. The orders are designed to bolster the safety of victims by having a court tell the person they fear to stop hurting, threatening, or having contact with them.

Each type of protection order and the steps needed to secure one are explained in plain language on a website called Ohio Legal Help. The Supreme Court partnered with Ohio Legal Help using grant funds to assist people in understanding their options.

For a domestic violence or dating protection order, visitors to the website learn how to find an advocate from a nearby domestic violence organization or an experienced lawyer. An advocate or a lawyer can assist with completing the forms, explain risks with protection orders, and point people to other services that may be helpful. There is also an interactive, self-help tool on the site that guides people through filling out the paperwork needed to request a domestic violence or dating protection order from a court.

The paperwork can be completed on a mobile phone, tablet, or computer. The person filling out the forms can stop and save along the way and return later, as needed. The site also has a safety button to quickly close the webpage to avoid danger if someone feared is nearby.

Once the forms are finished, the person requesting the protection order will need to go to the domestic relations court to file the request in person. The court will hold an emergency hearing that day to decide whether to issue an emergency protection order that will start immediately. In 2022, Ohio domestic relations courts received 24,876 requests for domestic violence and dating violence protection orders, according to Supreme Court statistics.

The demand for this kind of help is reflected in the number of people who visit the protection order section of Ohio Legal Help. More than 32,300 people went there last year. As of early November this year, more than 43,400 people had visited the section. Since the protection order pages launched in fall 2021, they have been the most visited family law topic on the website.

Protection order information and the entire Ohio Legal Help website are also accessible in Spanish.

Looking forward to early 2024, the interactive guidance for filling out protection order paperwork will expand on the website to include civil stalking and sexually oriented offense protection orders through a continued partnership with the Court and using a Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) grant from the Ohio Office of Criminal Justice Services.

Protection Order Guidance in American Sign Language Launched

On the Supreme Court website, protection order forms and instructions are available in English, Spanish, Arabic, Chinese, French, and Russian. The Supreme Court Domestic Violence Program and Language Services Section recently introduced a video series to assist deaf individuals who need to fill out protection orders.In the videos, produced with VAWA grant funds, certified deaf interpreters explain the domestic violence and other protection order forms in American Sign Language (ASL). The initiative arose from a 2019 Court survey that found that the second most commonly requested language in Ohio trial courts is ASL. In addition, some deaf individuals don’t read or write English and can’t understand from the standard written forms what protections to request or what a court might order and expect from them.

For the project, the Advisory Committee on Domestic Violence for the Court consulted with the two statewide service providers for deaf/hard of hearing victims of domestic violence, DeafPhoenix and DWAVE (Deaf World Against Violence Everywhere). The agencies worked with survivors and offered input about what would be most useful for their clients viewing videos of protection orders in ASL.

Court Enhances Offender Screenings With Online Tool

The Summit County DVIC launched a new tool a few months ago to continue improving the services they provide. It’s an extensive online resource focused on more fully orienting offenders to what’s expected if they participate in the DVIC program.

“Success cannot be expected by assuming that new participants know what is required of them on community control,” said Dena Hanley, Ph.D., who is working with the DVIC program to implement the online platform, called SAVS.

The court was looking for a more consistent way to screen participants for DVIC and to inform them about DVIC requirements, Hanley said. The SAVS platform supplements in-person candidate screenings and is designed to eventually track each participant’s progress through the program. The court also wants to identify each offender’s underlying issues, such as substance use, and the offender’s needs related to physical and mental health, employment, education, housing, and more. Hanley said one goal of the new tool is to match those needs to appropriate treatment and other resources.

Overall, the online tool gives the court more information to make the best possible decisions.

“It is a real-time gauge of individual progress as well as the DVIC’s process and outcomes,” Hanley explained.

Focus Remains on Victim Safety and Offender Accountability

With the new laws, court initiatives, and resources for victims, the hope is to keep victims safe. It’s also necessary to hold offenders accountable, find ways to change offender behavior, and curtail future violence. Anderson in Summit County noted that a domestic violence specialized docket delves into the underlying issues that lead an offender to act violently. That effort requires resources. Anderson, who has worked in the probation department for 24 years, said the available programs for domestic violence offenders fortunately have grown over time.

“I’ve seen resources provided for people who have never had services before,” Anderson explained.

Attitudes about domestic violence have changed as well. The violence inflicted by offenders is in no way excused. Yet society and offenders need to understand the harmful behavior to do something about it.

“Rather than being seen as pariahs of society, many of those who commit domestic violence now are seen as troubled individuals,” she said.

Helping offenders while working to keep victims safe ultimately will mean fewer people experiencing domestic violence. Walters of Henry County expressed her gratitude to the people who work with survivors every day. That sentiment can apply to the efforts of courts, specialized dockets staff, and domestic violence advocates across the state.

“It is the seeds that you plant that give us the strength to continue healing,” she said.

CREDITS: