School Attendance

More than 26% of Ohio’s K-12 students miss at least one day of school out of every 10. Ohio courts are finding ways to assist schools in addressing underlying family issues and steering students back to the classroom.

Just two weeks into a new school year, a fifth grader in Mahoning County hadn’t shown up to any classes. When Alexis Hura with the Mahoning County Juvenile Court was notified about the child missing school, she reached out to the family. The address and phone number on file with the school were no longer correct, and there was no record of the child being enrolled in school anywhere in the state, Hura said.

Through some digging, Hura and a school resource officer located someone in the student’s extended family who was able to provide a current phone number. The student’s mother had changed her number and moved without providing a forwarding address. A team from the school and juvenile court reached out to the mother to learn more about the student’s absences, and determined that some of the child’s basic needs weren’t being met. The family didn’t have stable housing, and there were safety concerns because the child was often left unsupervised. An aunt agreed to take over care of the child and engaged with the school-court team to give the child needed services, which included counseling.

“This student is now thriving and attending school regularly,” Hura said.

Hura is part of the Early Warning System, a partnership between the juvenile court and participating Mahoning County schools. The Early Warning System, which was put in place by Mahoning County Juvenile Court Judge Theresa Dellick about a decade ago, is a process for identifying warning signs that could hinder a student’s success in school. The tool flags students as “on track,” “sliding,” or “off track.” The goal is to prevent problems from escalating.

Poor school attendance is one warning sign tracked by the Early Warning System. School absences – both excused and unexcused – can indicate that a student or a family is encountering an obstacle keeping the student from attending school. And the reasons for missing school at any grade level are typically more complex than it may appear at first glance.

A school attendance toolkit developed by the Supreme Court of Ohio and Ohio Department of Education and Workforce (ODEW) explains that the difficulties often hindering attendance include a lack of food, clothing, stable housing, and transportation. A child might be suffering from a chronic illness, such as asthma, or a family member might be ill. Some students fear for their safety at school. Involvement with a child welfare system or a juvenile court can also factor into absences.

According to nonprofit Attendance Works, poor attendance can harm reading proficiency by the third grade. Missing school also is a leading sign that a student won’t graduate high school. The Supreme Court/ODEW toolkit noted that absenteeism ultimately affects job prospects, tax revenue, home and auto sales, and overall spending.

Statewide, recent data draws a concerning picture of school attendance. The number of students at public and community schools who were chronically absent in the 2022-2023 year – meaning, they missed more than 10% of class time – registered at 26.8%. It’s an encouraging drop from the 30.2% of Ohio students who missed that much schooling in 2021-2022, during the COVID-19 pandemic, but still well above the 16.7% reported for 2018-2019.

By a head count for the last school year then, there were more than 615,000 students, out of 1.6 million enrolled in Ohio, who missed at least 10% of their education, according to ODEW calculations. That’s one school day out of every 10.

Schools are the first to notice attendance issues, while courts traditionally become involved in the most extreme cases, which is when formal complaints are filed for truancy – excessive, unexcused absences. At the front end, schools can provide a solid foundation that encourages attendance to help students stay on track. That foundation includes ongoing communication with families and sharing community services that support attendance. But between the classroom and the courtroom, courts have partnered with schools to intervene and problem-solve to improve student attendance.

“There are many reasons behind why youth may be missing school. Many of our families are experiencing chaos in the home, trauma, poverty, homelessness, or a lack of role models.”

Early Warning System Relies on Computer Program

Judge Dellick said to launch the Early Warning System, they started small. The juvenile court hired one social worker to start. Each school that chose to participate established a team, which included the principal, school counselors, and other school staff, as well as the court social worker and the court’s director of the Early Warning System.

The court also enlisted a computer programmer to write a program to identify students at risk. The “on track,” “sliding,” or “off track” categories are generated from information about student attendance, behavioral issues, and academic performance that is entered into a dashboard. The student’s status for each issue is noted, and the dashboard also shows a combined overall category for the student.

The Mahoning County school-court team intervenes with students once they miss 30 hours in a school year – long before truancy triggers set by state law. The team reaches out to the student and the student’s family to find the barriers preventing the student’s success in school. Services for food, shelter, or transportation could be provided. Even something as simple, but essential, as access to a washing machine for clothing can turn things around for a family, Judge Dellick explained.

Overall, schools and juvenile courts are trying to steer children away from formal involvement in the juvenile justice system. Preventive approaches became central after the passage of legislation in 2017. The law prohibits suspending, expelling, or removing a student from school based solely on absences. It directed school districts to identify attendance barriers and ways to help students before a truancy complaint can be filed in juvenile court. Under the law, “habitual truancy” is defined as missing school without a legitimate excuse for 30 or more consecutive school hours, 42 or more hours in one month, or 72 or more hours in a school year.

Special Intervention Center Built to Assist Youth

To help students and their families, the Greene County Juvenile Court opened a Youth Assessment & Intervention Center in summer 2020 to assist those who are struggling, before students reach the truancy levels.

“Often the youth are labeled as ‘lazy,’ ‘dumb,’ or just ‘bad’ when, in fact, there are many reasons behind why a youth may be missing school,” said Mari McPherson, the center director. “Many of our families are experiencing chaos in the home, trauma, poverty, homelessness, or a lack of role models.”

Local school staff will refer students with attendance, behavioral, and other issues to the center. Law enforcement, community agencies, and parents also can make referrals. Participation is voluntary for students and their families, McPherson said.

“The youth undergo a variety of screenings to help assess where they are and what the family needs are,” she said. “We then have a multidisciplinary team meeting with community partners, during which we present the youth and family and discuss our findings. Oftentimes, the community is able to step in and offer services.”

If a family is experiencing domestic violence or doesn’t have housing, the center can help connect them with services, including shelter, she said. Children can be picked up for appointments with the center, and parents have been given gas cards to cover the cost to drive to the center or to other services. McPherson said the center offers monetary incentives, too, including for showing up to have an assessment done.

There’s also a mental health therapist on site who works with students or parents in individual or family therapy, she noted. The facility offers group programs for students, and for parents there is the “Parent Project,” a multiweek program focused on addressing school absences, drug use, and gang involvement. The students in Greene County’s seven school districts who missed 10% of classes in 2022-2023 dropped close to 5% from the year before.

“The intent with all of these services is to treat each child as holistically as possible in order to address all of their needs rather than take punitive measures against a child,” McPherson explained.

Finding an alternative to punishment was a driving motivator for Judge Dellick, too. She mentioned a student who missed school three days in a row and was suspended. The judge said the student received an F grade in his classes for each suspended day, he wasn’t permitted to make up the missed assignments, and he was barred from participating in school activities during his suspension.

“Such onerous and compounded sanctions eliminate any desire to catch up, let alone attend, school,” Judge Dellick said. “These sorts of excessive sanctions have the reverse effect intended by the school – the student sees no hope in improving and either drops out or drops off, just going through the motions of school.”

Today in Mahoning County, nine school districts out of 14, plus two charter schools and a career/technical school, participate in the Early Warning System. In 2020-2021 and 2021-2022, the five non-participating school districts had three times more truancy referrals than the nine participating districts. For the 2022-2023 school year, the total truancy referrals for each group were about even.

In 2022-2023, the average rate of chronic absenteeism for the five non-participating school districts was 38.1%, according to ODEW data. For the nine that participated, the average was 22%. Judge Dellick noted that they are exploring new measures to cut down the 22% further.

Other School-Court Teams Take Action When Truancy Triggers Met

In other Ohio counties, absence intervention teams mobilize once a student hits the habitual truancy markers set in state law. In Franklin County, the team includes school staff, a parent, and the student. Also part of the team is a truancy officer employed by the Franklin County Juvenile Court who acts as the court’s liaison.

As part of the intervention plan, the team identifies resources and offers referrals to services for the student and family. Often, that’s all it takes to resolve the attendance issue, said Julie Troth, director of the court’s Juvenile Programs and Services. She said seven out of 16 school districts in Franklin County participate in TIPP, the Truancy Intervention and Prevention Program, and the court now employs 10 truancy officers for the program.

“In mediation, we don't make a plan for the student, but allow the school, student, and family to come up with the plan that they all are agreeable with.”

The results are notable.

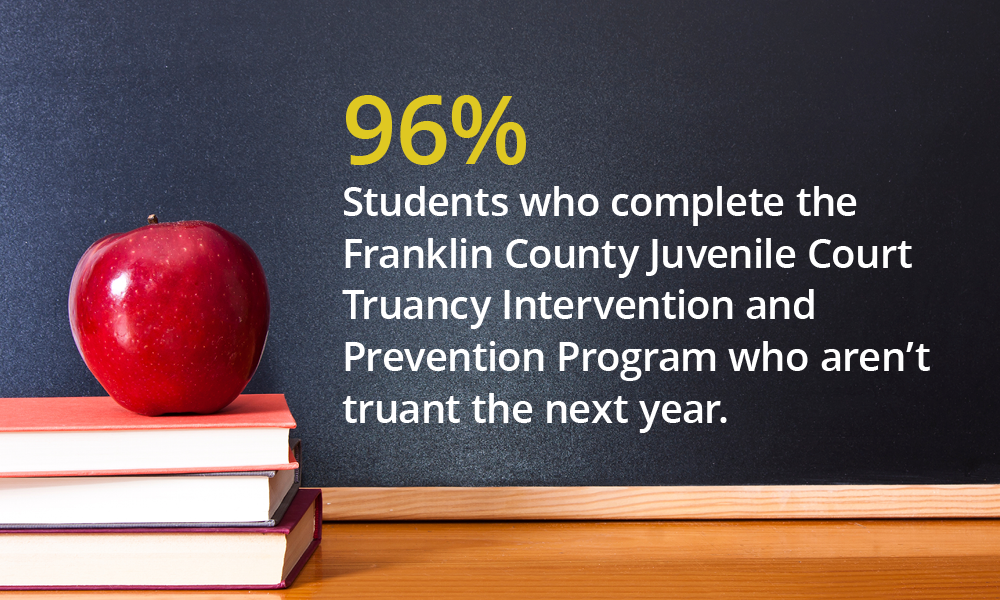

Since 2017 when the program launched, about 1,800 students from participating schools reach a truancy marker each year and are referred to TIPP. Truancy officers monitor student attendance at 30-, 60-, and 90-day intervals. If a student fails to make progress on their intervention plan, habitual truancy charges are filed with the juvenile court, Troth said. Of the 1,800 students referred to court programs annually, only about 300 end up in juvenile court because a truancy complaint was filed. Troth noted that 96% of students who complete the intervention plan developed through TIPP also successfully avoid truancy issues the next school year.

As far as chronic absenteeism, the rate at the seven participating school districts dropped from 29.4% in school year 2020-2021 to 24.4% in 2022-2023.

Destiny Jones, a truancy supervisor, has seen firsthand the impact the program has made for students and their families.

In late 2022, a 10th grader named José was flagged as missing 109 hours of school. A meeting was held to improve his attendance. It included José, his mother, the principal, a school guidance counselor, a court truancy officer, and Jones.

José’s mother had lost her job, the team learned. She lacked consistent childcare for her children, causing her to miss many days of work. Without an income, the family was facing an eviction. José had found a job to help pay the rent and also took care of his siblings. That’s why he was missing school.

With the team’s help, the family was linked with immediate food assistance. José’s mother was connected with a local organization that helps with rental assistance and provides employment resources.

Jones spoke with José about his work schedule because he had been working during school hours. They came up with a plan to get his schedule changed to after school. José’s mother found a job at a local hotel, secured daycare for the children, and got caught up on the rent.

“At the 30-day check-in, José had only missed two unexcused days, which was a huge improvement,” Jones said. “At 60 days, he had not missed any additional days, and his grades had risen from Fs to Cs.”

Success Achieved With Mediation Between Students and Schools

Other Ohio juvenile courts take a different tack by focusing on mediation, which can be used to develop an absence intervention plan. The purpose of a mediation is to address a student’s absences in a supportive, non-judgmental, and non-punitive way – with the help of a neutral party, a mediator, in a confidential setting.

Raymon Payton has been guiding mediations on attendance issues for the Clark County Juvenile Court and local schools since his hiring at the court in 2000. There are eight school truancy officers, and they recommend students to the court for mediation, Payton explained. Some schools have set times each week for the mediations, and the court mediators schedule that school’s cases at those times. He said typical mediations are conducted in person at the schools – with Zoom and phone options if needed.

Offering incentives and opportunities for organized social activities has worked well in mediations. Payton said students have been enrolled in job readiness courses and have gotten involved in Project Jericho or On the Rise. Students in Project Jericho participate in visual and performing arts projects. For On the Rise, students help on a farm with gardening and animal care. Payton said structuring student free time has helped improve school attendance.

For the last full school year, 348 mediations were scheduled for students, and 75% showed significant progress with their attendance. The mediation program’s success stems from the long relationship the court has had with the schools over time and the neutral role the mediators play, Payton noted.

“We don’t make a plan for the student, but allow the school, student, and family to come up with the plan that they all are agreeable with. We may mention what has worked with other families in similar situations,” he said. “We’re very transparent with the families about the harsh realities of the student continuing to not attend school and what those potential consequences look like.”

Working With Schools Puts More Students on Right Track

The Supreme Court and ODEW emphasize the value of collaboration between courts and schools for good school attendance. Courts and schools across the state are encouraged to meet at least annually. By working together and sharing information at the start of the problem, courts have the benefit of knowing before a formal complaint reaches them what steps have already been taken and the root causes of the absences.

Troth said fostering connections with the Franklin County schools was essential to launching TIPP. She and a spokesperson from the local Educational Service Center went to the schools and met with district superintendents to encourage their buy-in.

Courts also contribute funds to make the efforts work. The Franklin County Juvenile Court pays half the salary of the school truancy officers, 100% of the officers’ employee benefits, and 100% of the costs of equipment, such as laptops, printers, and uniforms. These court-covered expenses are a substantial savings to the schools, Troth said. On behalf of the court, the truancy officers handle many of the logistics – locating all attendance records, making intervention attempts with the students, completing truancy complaints for the court, and attending court hearings.

The Early Warning System in Mahoning County was initially funded by a federal grant awarded to the juvenile court. Once the grant funding ended, the court believed in the program’s value and built the expenses into the court budget to ensure continuity, Judge Dellick said.

“Your budget is your policy,” she noted.

For courts that want to try a program like theirs, Judge Dellick points out that each school district has its own culture. There are also different needs in rural, suburban, and urban districts.

“Courts have to modify the approach for its school districts or county,” she said.

McPherson in Greene County suggests, “Don’t be afraid to be flexible.”

What works with one family may not with another, and creativity can help them solve their specific problems, she said.

“Our goal is to get to the reasons behind the attendance issues, surround a family with services and support, then step back and let the family thrive.”

CREDITS: