Standing for Victims

For people who’ve experienced violence by an intimate partner, help can be found from many organizations. Among them are advocates who guide domestic violence victims through the courts toward healing and justice.

Victims of violent crime can be hesitant to pursue charges or testify in court – thinking they might not be believed or because they’re afraid of retaliation. For people who encounter violence by someone they know, the concerns compound. They may worry the offender won’t be convicted or, alternatively, want to protect the offender because of their relationship. Having someone to provide direction throughout the legal process can be beneficial to victims, and for holding offenders accountable.

In fact, victims who connect with a victim advocate are more likely to participate in prosecution and to think that the court process has been safe, fair, and responsive to their needs.

That was true for a woman who was attacked by a man while they were on a date in Meigs County. Afterward, she felt alone and scared. She lived outside the county, and the man had fled. The investigation stalled. She reached out to a Meigs County group for domestic violence victims regarding a civil protection order against him. While assisting the woman, the group called victim advocates in the county prosecutor’s office.

Victim advocate Shelley Kemper contacted the woman, collected information, and shared it with prosecutors, who indicted the man for felonious assault and abduction. With Kemper’s guidance, the woman testified at trial, which led to a conviction.

Throughout the legal process, the woman was updated about each step of the case, and Kemper was by her side every day in court. The woman told Kemper, “I would have given up a long time ago without your help.”

Across Ohio, victim advocates in many settings – community-based nonprofits, domestic violence shelters, mental health agencies, and others – stand ready to assist people who’ve suffered violence by someone they know. A good number of these advocates work in prosecutor’s offices. About 94% of county prosecutor’s offices have staff dedicated to helping victims, according to the Ohio Victim Witness Association. Victim advocates are also stationed in prosecutor’s offices at the municipal court level.

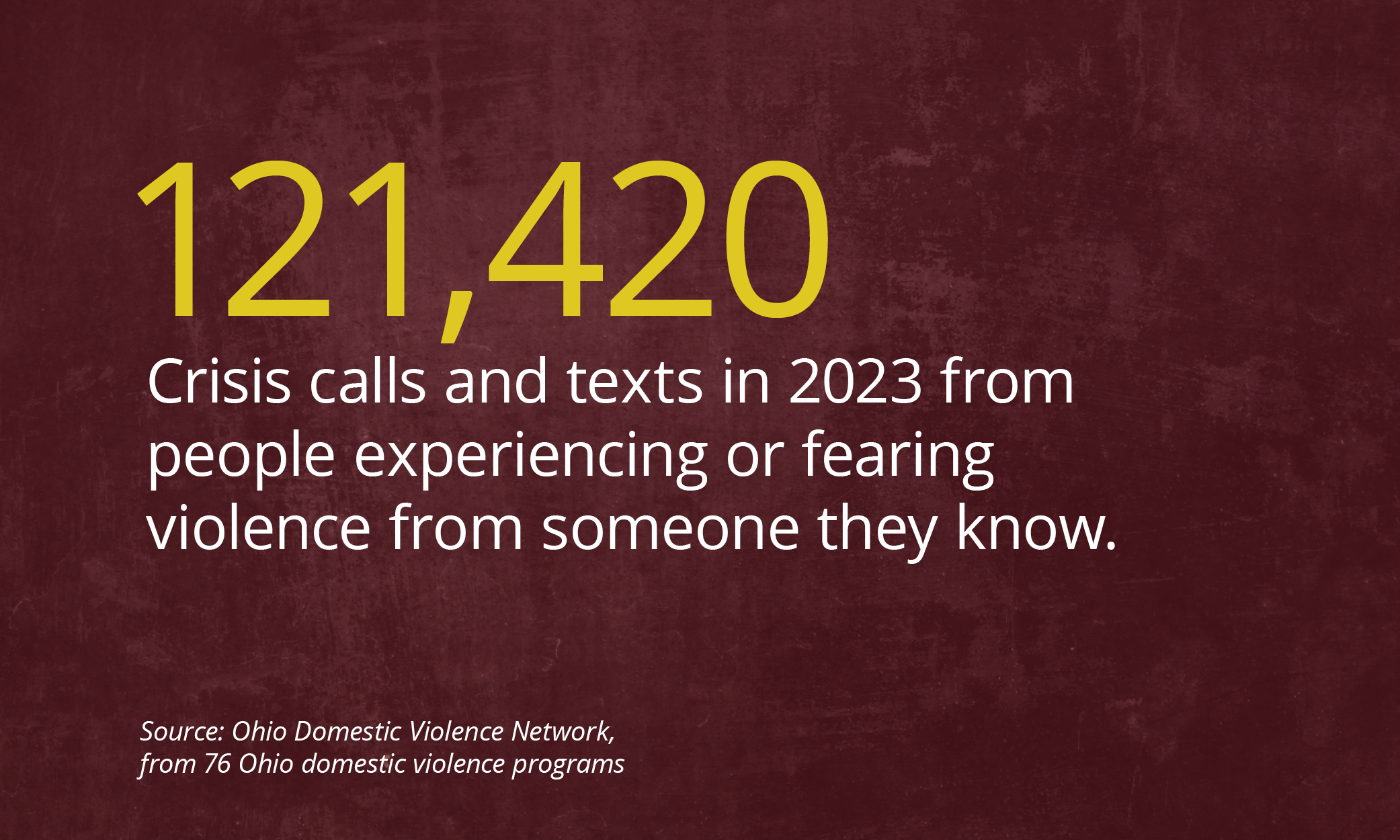

The need is unmistakable. Each day last year, people experiencing or fearing violence from someone they know made 333 crisis calls, texts, and webchats to domestic violence programs that are part of the Ohio Domestic Violence Network.

Victim Rights Form Triggers Initial Contact

In Meigs County, the victim advocates first learn of incidents from law enforcement. An officer or the victim completes a victim rights form, and law enforcement sends it to Kemper and the other advocate, Katelyn Dillard. The person can be a victim of any crime. Of the 461 new victims in 2022 who they worked with, 125 of the cases involved domestic violence offenses.

The form alerts Kemper and Dillard that it’s time to quickly reach out to the victim.

“We tell the victim we were notified of the domestic violence incident and are here to answer questions, help with the legal process, and find medical treatment if needed,” Kemper said.

It’s the start of an ongoing conversation, which includes informing victims about the first court hearings that will take place. Among the criminal offenses that might be charged based on domestic violence are felonious assault, domestic violence at the misdemeanor or felony level, or strangulation. The cases show up across different courts – common pleas, county, municipal, and juvenile – which Kemper and Dillard divide between them.

Kemper said after that first conversation, they continue phone contact with each victim, providing updates on the case and responding to questions. The victim is often scared after the physical violence. Also, it’s not unusual for suspects to call victims from jail after an arrest, pressuring them to drop the charges, Kemper explained. These situations make the early conversations with advocates crucial.

“Victims sometimes talk more early in the case,” she said. “We learn a lot more about the circumstances.”

When a victim visits the advocates’ office, the meeting typically includes discussing the case with a prosecutor, too. It may take time for the victim to be willing to talk about what happened. Kemper said that it’s essential to maintain communication and be flexible to meet victims when they want.

“We ask the victim to come in only when they are ready,” Kemper said. “It’s important to be there, and listen to their story no matter if it relates to the court case or not.”

Jessica Haug, a victim-witness advocate in Muskingum County, reiterated the value of early discussions. She said she and Lea Ann Tignor, the victim-witness coordinator, are able to gather a lot of background information to identify services or strategies to tackle the varied problems the victim is confronting.

“We don’t focus on the attack,” Haug noted. “We ask, ‘How do you know the person charged? Do you have kids? What was your relationship like before this happened?’ This approach gives us the bigger picture. Because each case is different.”

Full Scope of Victims’ Lives Need To Be Seen

The Muskingum County advocates learn of a domestic violence-related case once law enforcement files a report with the prosecutor’s office. Tignor and Haug work with all crime victims. Last year for domestic violence incidents, they assisted in 134 cases.

In their ongoing discussions with victims, Haug and Tignor always engage with them about their lives beyond the case. They will inquire about summer plans; how school, sports, or other activities are going for their children; and family pets. Haug said it’s important to be able to handle a lot of complex emotions and be patient with victims.

“Their domestic violence situation doesn’t define them as people,” she said.

Victims also face immediate concerns that often dominate conversations with the advocates before legal processes are explained.

“They want to know what will happen with their kids,” Tignor said. “Whether they can talk to the defendant. Where the defendant will stay.”

Haug added other stressors for victims when the suspect is their partner: “How they will support themselves, keep their home, and pay bills.”

The prosecutor-based advocates will connect victims with community partners and resources for assistance with these issues.Advocates Explain Nuances of Charges and Court Proceedings

As the case progresses in court, the advocates sit in on the proceedings, from arraignment or preliminary hearing through trial, if there is one. Kemper said, though, that a victim may not attend, especially early on, because the physical encounter leading up to the arrest or charges are still fresh. Arraignments after charges are filed typically happen quickly – within a day or so.

“Some victims want to attend the arraignment, but others don’t want to see the suspect,” Kemper said. “Our role is to go with the victim to court, or to go to court on behalf of the victim.”

Dillard noted that before a victim attends court, she will discuss what happens in the courtroom as well as possible scenarios for the unpredictable parts of a proceeding. Victims also might need to navigate different aspects of the domestic violence incident in different courts – such as attending a criminal case in common pleas or municipal court, or filing for a civil protection order or handling issues regarding children in domestic relations court. All of it can be confusing and time consuming. The advocates are there to steer victims through the complexities of the justice system.

Dillard said that misdemeanor cases move fairly quickly. Hearings may be scheduled soon after an arraignment. Depending on the misdemeanor, trials must be held usually within one to three months, if speedy trial rights are not waived. While waiting in court for a case to be called for a hearing, Dillard will meet victims in the hallway and talk, keep them company, and try to make them comfortable with the process.

For felony charges, more time is built into the common pleas court process, Kemper said. She will have the victim visit their office to discuss the case. Forms for medical releases and restitution can be filled out. A common area of confusion is the difference between misdemeanors and felonies, and how that changes possible sentences.

One increasingly frequent topic of discussion with victims is the criminal charge for strangulation. The recently created criminal offense took effect in April 2023 and is a felony. Along with questions about the seriousness of the charge and potential consequences for the offender, victims also can be confused because they don’t recall being strangled, or they don’t understand the aftereffects of strangulation. Haug mentioned there can be “hidden side effects,” such as seizures, and other ongoing symptoms and health problems.

Questions can be addressed with the prosecutor and the advocates.

“We will meet with victims several times throughout the case,” Kemper said.

Once a court hearing is over, the advocates go over everything that happened in the courtroom again because the legal system is foreign to most people, and the circumstances are stressful. Haug said she’ll also explain the meaning of the many legal terms and spell out next steps.

Another key role for advocates is facilitating the “flow of information back and forth from the victim to the prosecutor,” Tignor said. Although prosecutors always meet with victims, advocates spend more time with each victim and develop bonds.

“Our work with victims makes the prosecutors’ lives easier,” she said. “We know the victims. We know what they want.”

Connections to Suspect Can Create Complications

Throughout the course of the case, the advocates will grapple with the range of many victims’ contradictory emotions. Victims who are married to the defendant, in a romantic relationship, or have children together may feel afraid, but also may worry about the consequences of a conviction to the person they care about. They may want the violence to stop but know a conviction could prevent gun ownership, lead to the loss of a job, or prevent the ability to pursue future careers. These consequences can have a major impact on the victim’s life as well.

Tignor said it’s imperative not to attack victims for their relationship with a defendant.

“The choices a victim makes about continuing with a case can change a defendant’s life or the victim’s life,” Tignor explained. “You have to respect that the defendant and victim often have a long history. We always ask victims what their thoughts are about what should happen.”

The entirety of the experience can be overwhelming for victims. Deirdra Lashley, executive director of long-term shelter Bethany House in Toledo, said victims have been traumatized by the violence and can experience traumatic feelings again during the court proceedings.

“They have mixed feelings for a lot of reasons they can’t even say,” Lashley explained.

Victims might also retreat from going forward with a case because of pressure from the suspect’s family. Those family members may call or text, pushing for a victim to not talk to prosecutors or to drop charges. Dillard said it happens “a lot.”

“If the victim doesn’t need to be in contact with the family member, I tell them to report it to law enforcement,” she said.

That produces a legal record of the interaction. She also discusses obtaining a civil protection order against the person, if needed.

Of course, pressure from the defendant or family members doesn’t necessarily occur during the advocates’ work hours. Neither do the difficult times when a victim could use support. In Meigs County, the advocates decided to allow victims to connect with them on Meta’s Messenger app. It doesn’t require providing personal phone numbers, and it opens a channel of communication with victims that the advocates can easily monitor when possible.

“Victims can reach out off hours,” Kemper said. “It has been a real help for us in helping them outside of work hours and on weekends.”

Victims Reluctant To Testify Want Help With Other Difficulties

Even if a victim doesn’t wish to move forward with charges, the prosecutor’s office can do so if the office thinks it’s warranted. Kemper said, though, that talking to victims often reveals an underlying concern that they want addressed outside of court.

“Victims often say, ‘I want to dismiss the case, but he needs help, has a drug problem,’ et cetera,” Kemper said.

Advocates explain the role courts can play in resolving these issues. Kemper emphasizes to victims that the court can’t order assistance for the defendant without reviewing the case and charges. And a defendant is more likely to accept help and do what’s required if it’s court ordered, Tignor noted.

Haug agreed, pointing out that courts can present more options and provide access more promptly. Court orders enable quicker hospital evaluations, speed up the process for getting into counseling, and lead to greater responsiveness from other outside resources, she said.

“Being in the criminal justice system makes the situation more serious,” Haug said. “It jumpstarts the process.”

As part of resolving issues, a prosecutor might propose probation instead of jail or prison or agree to dismiss a case on certain conditions, which could include treatment. These decisions depend on the evidence and input from the victim – with any agreement ultimately needing approval from the court.

Advocates Inside and Outside Courts Work Together

Staffing and resources for victim advocates’ services aren’t without limits. Advocacy groups outside of the courts become instrumental partners. Prosecution-based advocates will refer victims to community-based advocates for support groups, shelter, and other services.

Lashley at Bethany House said while its staff don’t specialize in matters inside the courtroom, they give assistance in other ways related to the cases. That includes setting up basic logistics when victims are heading to the courthouse.

“We become a support person when the victim is going to court,” Lashley said. “We help them be prepared – telling them where to park, where to walk into the courthouse, who to meet with, who their allies are.”

Stephanie Potter of Bethany House added that safety planning is another important piece.

“We may contact the sheriff for transportation of victims to court, and make plans for safety before and after court,” she said.

If the victim is driving, the advocate will walk with the victim to and from the car, Potter said. If someone would normally take the bus, the shelter can instead arrange for a ride-sharing service for greater safety or have someone drive them to and from the courthouse.

Inside the courthouse, advocates will stay by victims in lobbies or waiting areas to help them feel safer when the suspect or other family members are there, Potter said. Or they’ll move into a different room if necessary.

All of these steps build on the support from advocates in prosecutor’s offices that together can benefit victims going through an unfamiliar legal process and difficult circumstances. Kemper noted that a local emergency shelter and resource referral group stepped in to assist with securing protection orders. They also rely on Southeast Ohio Legal Services for victims’ legal needs, such as filing for divorce, help with custody orders, and more. In Muskingum County, Tignor said victims receive direction for housing, protection orders, and other resources through a local domestic violence shelter.

Advocates’ Contributions Support Victims and Justice

It’s important for advocates in the legal system and the community to build trust and rapport with victims. That trust and rapport creates a safe place where victims can talk when ready, giving them support and moving cases toward ensuring justice. Potter explained that the best advocates are fair, compassionate, good listeners, transparent about the legal process, and effective at connecting victims to the services they need.

“Also, being nonjudgmental, so that victims can become whole and healthy, and life can begin again for them,” Potter said.

Lashley stressed the value of the support that advocates give to victims not only at the beginning when they are first seeking help, but also throughout a case.

“Advocates make or break whether a victim will participate in a court case,” she explained. “They’re a consistent person who will walk with victims through the process.”

CREDITS: